Earlier this year I wrote that investors need to be careful not to get sucked in complacency about the apparent rebound in the U.S. stock market.

My argument was that the underlying fundamentals of the economy don’t really justify the price appreciation we’re seeing.

Instead, it’s an increasingly open secret that stock price appreciation is based almost entirely on the Federal Reserve’s decision to halt interest-rate hikes. And also to slow down the so-called “winding down” of the junk assets it bought in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

If that’s the case, stock valuations could easily reverse themselves unexpectedly.

A recent comment on the structure of the U.S. stock market prompts me to double down on that warning.

Stock prices are going up, yes.

But ordinary retail investors like you and me are leaving the stock market in droves.

That raises two uncomfortable questions: Who’s left in the market … and can we rely on them to keep stock valuations rising?

The answers will shock you…

Who’s Got the Hot Potato? Not Us

Legendary investor Warren Buffett once said that you find out who’s naked when the tide goes out.

Based on recent development of the buy side of the U.S. stock market, you’d be well-advised to check the state of your bathing suit.

A February survey of fund managers — by Bank of America Merrill Lynch — reported that money managers holding more assets in cash than usual outnumbered those holding stocks by 44%. That’s the biggest margin since January 2009.

Driving that shift is a large-scale retreat from equities by institutional investors like pension funds, and by Main Street investors like you and me.

In February, investors pulled $7.33 billion out of the U.S. stock market. The bulk of that money moved to the bond market.

And yet, the major U.S. indexes are up about 11.5% for the year so far.

How do we square that circle?

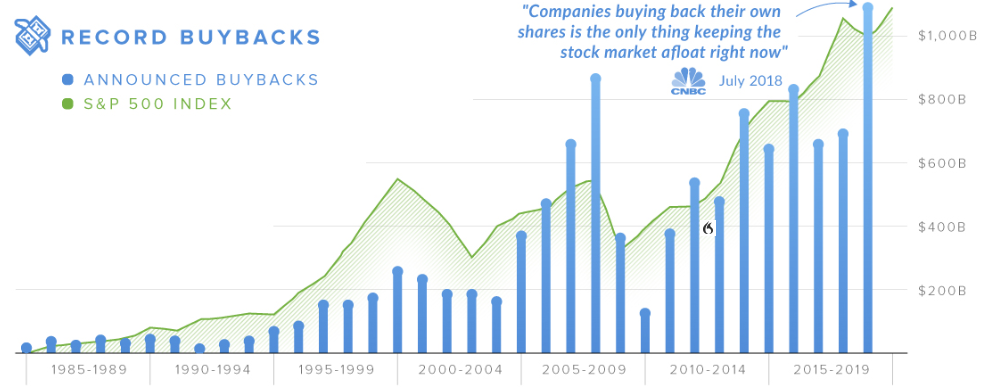

The simple answer is that American corporations continue to buy back their own shares at a historically unprecedented rate. They are the ones propping up the stock market — not us.

In the fourth quarter last year, U.S.-listed companies bought an estimated $240 billion of their own shares, according to an analysis by Goldman Sachs. That’s 60% higher than during the same period in 2017.

And more buybacks are on their way.

Answering the Wrong Question

I’m on record as being opposed to large-scale stock buybacks.

Many analysts — including some of my own colleagues — reject my negativity. They say stock buybacks are a legitimate way for companies to return money to their shareholders.

But that’s not really the question I’m asking.

I’m concerned about what the rise in stock buybacks says about the underlying economy … and therefore about the future of your investments.

The basic job of senior corporate executives is capital allocation. They decide on the best use of the company’s money.

When those executives decide the best use is to consume it rather than invest it — which is essentially what stock buybacks do — that tells me those executives don’t have a lot of faith in the future of the economy.

And that’s what worries me. If American corporate executives would rather “eat” their company’s money than invest it in growth opportunities, how can we expect the stock market to continue its upward climb?

After the Party, the Hangover

Remember all the talk around the time of the big tax cuts at the end of 2017?

The Trump administration said the cuts would produce a corporate spending spree, turbocharging wages, investments and growth.

Didn’t happen.

Year-on-year business investment growth fell from a high of 8.5% in the second quarter of 2018 to 0.8% in the third. Figures for the fourth are unlikely to be any better.

On the other hand, corporate stock buybacks hit a new record in the fourth quarter of 2018:

I don’t dispute that corporate executives are within their rights to buy back their own shares. It’s not illegal — at least not since the Securities and Exchange Commission changed the rules in 1982.

But if the people whose job it is to allocate capital think it’s a much better idea to pull money out of their companies than to reinvest it, how safe are your investments?

A House of Cards

The surge in buybacks reflects a fundamental shift in how the U.S. stock market operates.

Corporations are now the single largest source of demand for U.S. stocks. That’s practically the only thing sustaining the bull market as political, international and economic uncertainty grows daily.

But it also reflects a massive change in the global financial system in the decade since 2008.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the world’s central banks — institutions created by government to serve the needs of all people — rescued the financial system by buying up practically worthless investments from the private sector. If those investments had remained on the books of banks and corporations, they would’ve gone insolvent.

In the decade since, central banks like the Federal Reserve have held onto those junk assets, and kept interest rates as low as possible. It’s a massive subsidy intended to shield the economy from the effects of the bad decisions made by banks and corporations before 2008.

That subsidy has been the driving force of the long bull market in stocks. And increasingly, the main beneficiaries of that subsidy are the executives and shareholders of companies buying back their own shares.

The bottom line is that what’s left of the U.S. bull market is based on an accounting trick — a “put” by the world’s central banks, who’ve evidently decided to continue subsidizing the private sector by suspending the liquidation of their balance sheets.

For investors depending on passive investments in stock market indexes like the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSE: SPY) to keep their portfolios growing, this is a dangerous situation.

Your wealth and future prosperity depend on the decisions of people in the boardrooms of U.S. corporations and in the hallowed halls of the Federal Reserve.

Do you trust those people to do the right thing? I don’t. They’re looking out for their own interests.

That’s why you must be much more selective in your choice of investments in 2019 — and The Bauman Letter is here to help you do it.

Kind regards,

Ted Bauman

Editor, The Bauman Letter