As the Treasury yield curve goes “inverted” and Wall Street panics, I break down the practical results of yield curve inversions, the prospects of a near-term recession and what you can expect for your portfolio in 2022.

Find out this and more in your Friday edition of Big Picture, Big Profits.

Transcript

Hello everyone. It’s Ted Bauman here, editor of Big Picture, Big Profits, and of The Bauman Letter. Before I proceed, remember that you can subscribe to either or both of these by clicking on the little “i” above my left shoulder, that is essentially an offer. You can either sign up for our free newsletter, which is Big Picture, Big Profits, which gives you access to these videos and also written articles by myself and Clint Lee, and sometimes other people, or The Bauman Letter, which gives you a 12-month moneyback guarantee. That’s where I make stock recommendations and also essentially keep tabs of the market and keep my readers updated on what’s going on with their investments.

Now, today, I want to talk about two things, which I believe the mainstream financial press are reporting poorly. I believe that they are leaping to conclusions and really generating click bait headlines that don’t necessarily reflect what’s going on underneath the hood, if you like, of the economy and of the financial system. I think that there are interests behind this. Part of it is that I think the mainstream financial press finds it easier just to use lazy platitudes and just follow the herd as it were. But on the other hand, I think that there are some financial interests that prefer that people think of things in one way as opposed to another, because it’s good for their bottom lines.

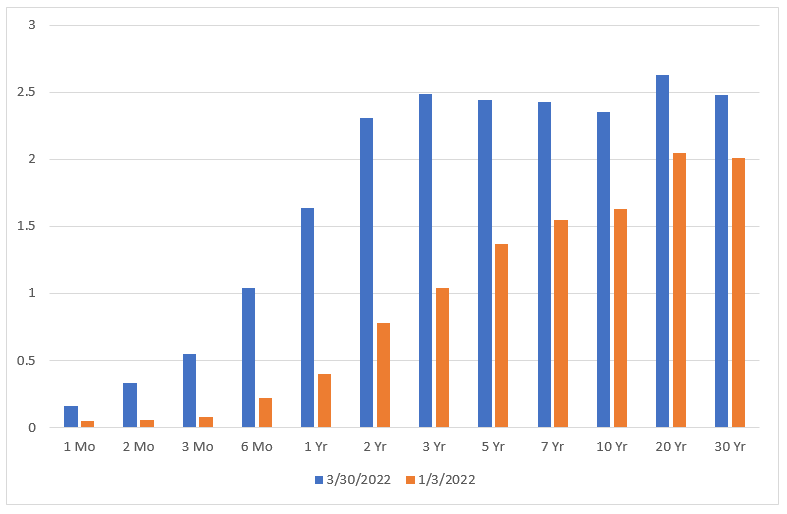

Let’s start with the yield curve. What’s a yield curve? A yield curve is essentially this. Here is a chart that shows yield curves, basically two of them.

One is from the first trading day of this year, that is the 3rd of January. And the second one is from the 30th of March, the day that I recorded this video. Now, what it’s showing you are the rates on different maturities. So starting with one month through two, three and then right across up until 30-year bonds, what you can see is the amount of yield that you get at current rates. And those rates, of course, are set by market trading. Those are not the coupons at which the bonds were initially issued. They are the yields that are being set by people buying and selling the bonds. And, of course, the lower the price of a bond, the higher its yield goes, which means that people are trying to get rid of them rather than buy them.

Well, first of all, it tells us that all interest rates across the yield curve have risen since the beginning of the year. But those at the short end of the curve, particularly the mid range, in other words, from one, two, three and five year, those have risen much more than longer-term yields, particularly the 10 year 20 and 30. Now, why is that important? Well, in economic and financial law, an inverted yield curve, which is basically one where short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates is a sign that the central bank might be making a mistake. In other words, the idea is that by raising interest rates that the Federal Reserve might be inducing a recession.

If you’re going to get a recession coming up in the future, that means that sure, in the short term, you don’t want to be stuck with bonds that yield less than the inflation rate or what the Federal Reserve’s target price is. So, you sell short-term bonds, but then you buy long-term bonds because you think that the economy is going to slow down in the future and you’ll make better returns by holding long-term bonds like tens, twenties or thirties. So essentially, when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates, it’s an assumption that the Federal Reserve is making a mistake and will induce a recession, which will then lead to better returns for long-term bonds.

Now, maybe it’s not a mistake. Back in the 1980s, Paul Volcker, the head of the Fed engineered a recession that vanquished double-digit inflation. And it did so, or he did so by raising interest rates to the point where unemployment hit nearly 11%. Now nobody’s accusing the Fed of having done that inadvertently or by mistake in that point. In other words, it chose to pay the high price of controlling inflation by engineering a recession. Now that’s not something that bankers want to do today. As much as they talk about their duty to support jobs and growth, they want to reduce prices basically to try to bring stability back to the economy. They want to do so without causing a recession, which is what people call a soft landing.

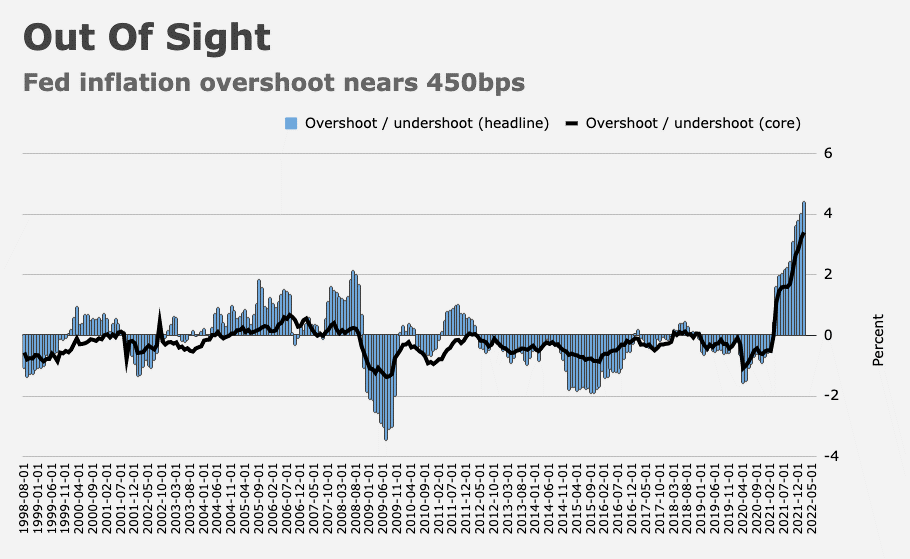

Now, why are they doing this? Here’s a chart that shows recent inflation.

It’s going back to 1998. So you can see it in comparative terms. But clearly, in the last 30 years, we’ve never, ever had inflation like this. You can see that both headline inflation and core inflation, which basically strips out energy and food and other things like that is just way above where the target is. So this is not the entire inflation rate. This is the overshoot, relative to the Fed’s target rate. And now the Fed is having to figure out how to reign this in. And the only tool it has in its arsenal is to raise interest rates.

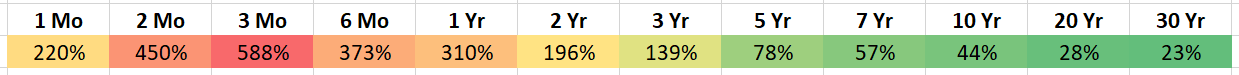

Now here’s a picture, rather, it’s a table that I put together that shows the current rate of change or the rate of change since the beginning of the year in the yields on various maturities.

As you can see, the biggest gains come in that sort of very short term, really from one month up to a year, that’s where we’ve seen triple digits. We’re also seeing triple digits in the two- and three-year, but nothing like the very short term. And that, of course, reflects the fact that people have been dumping short-term bonds as quickly as they can, because they don’t want to get stuck with them at yields that are below what the Fed is going to be doing in the short term. And so that’s why those yields have risen.

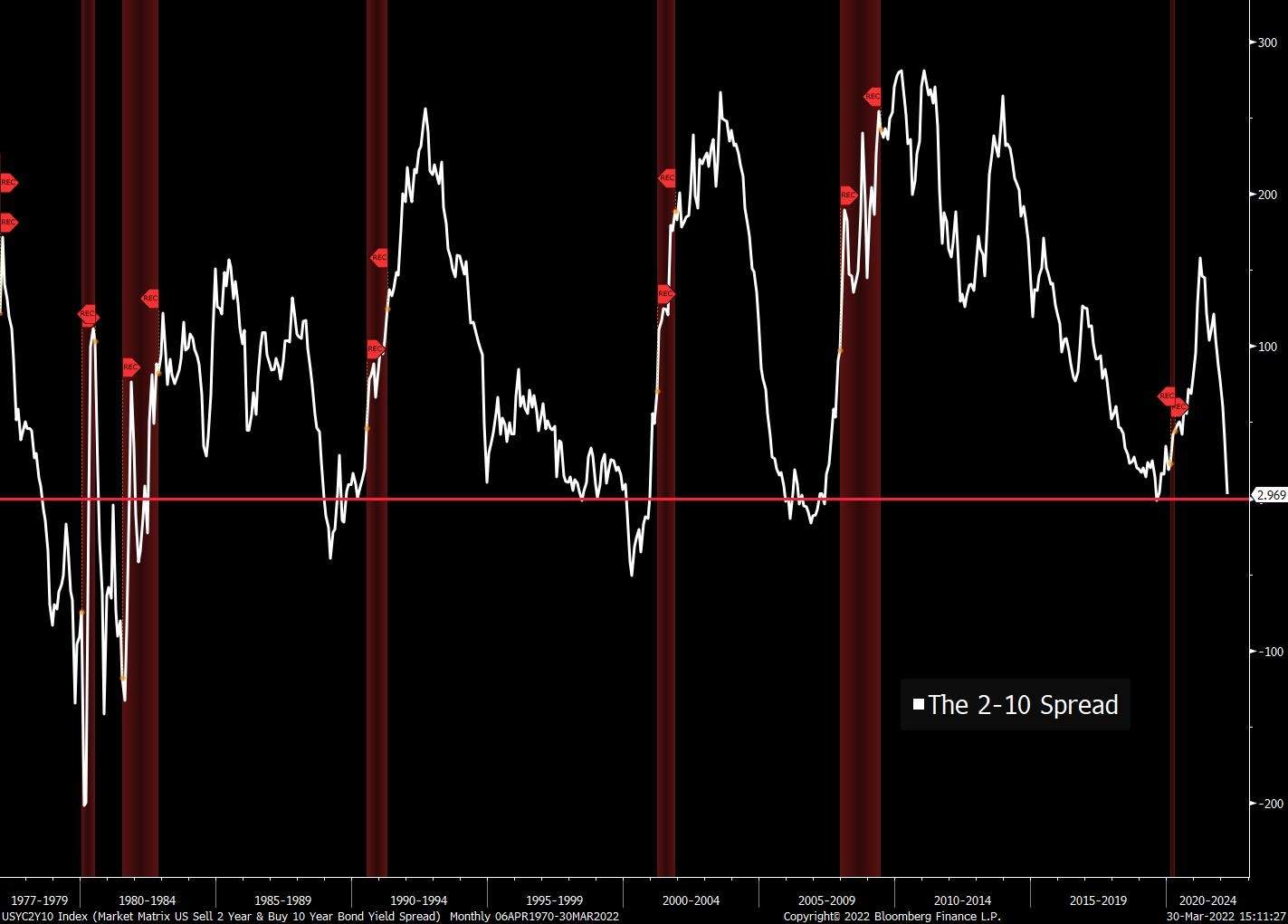

Now, yields have risen right across the whole curve, but the point is that short-term yields are rising much faster than longer-term yields. The two, for example, is up by nearly 200% since the beginning of the year. And in other words, that’s basically almost a doubling of the interest rate, whereas the 10 is up by only 44%. Now when you have that kind of action, when the two is up very strongly, but the 10 less so, this is what happens. This is what’s called the two and 10-year spread:

And it shows basically the difference between the two. When the two is basically higher than the 10, then it falls below that red line. That’s, what’s called an inversion in the two to 10 spread. And look at the track record. Every time that happens, every time the two- to 10-year spread falls below parity, basically right at that point, you get a recession. And that’s why people say that this is such an effective way of predicting future recessions. So look where we are right now. It’s just about to plunge below it. It did actually plunge below it temporarily a couple of days ago, but then it’s pulled back a little bit. In other words, the two has fallen and the 10 has risen, and that has prevented us from falling below that. But you can see the trend, that’s where we’re headed.

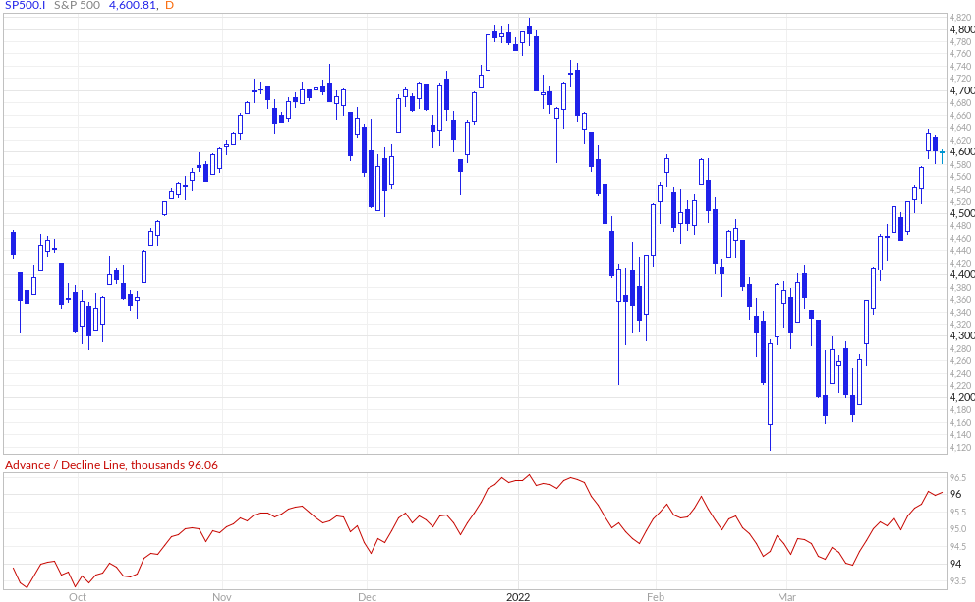

Now, remember this reflects expectations in the bond markets. It’s not something that reflects actual economic activity, because actually economic activity is not that bad. We still have a strong employment growth. We still have, as I’m going to talk in a moment, very strong profitability and we still have a rapidly growing economy. So here’s the funny thing. Here’s a chart that shows essentially the advance/decline line for the S&P 500:

The advance/decline line is basically the number of stocks that are rising in price versus the number of stocks that are falling in price. And after a big pullback, since the beginning of the year, if you look on the right-hand side, you can see that the number of stocks that are advancing has increased very substantially relative to those that are declining. That red line in the bottom shows that we are basically heading back to the kind of conditions we had earlier this year when we reached a peak, I believe on the 3rd of January. So even though we have the potential for an inverted yield curve, the market doesn’t seem to worry about it.

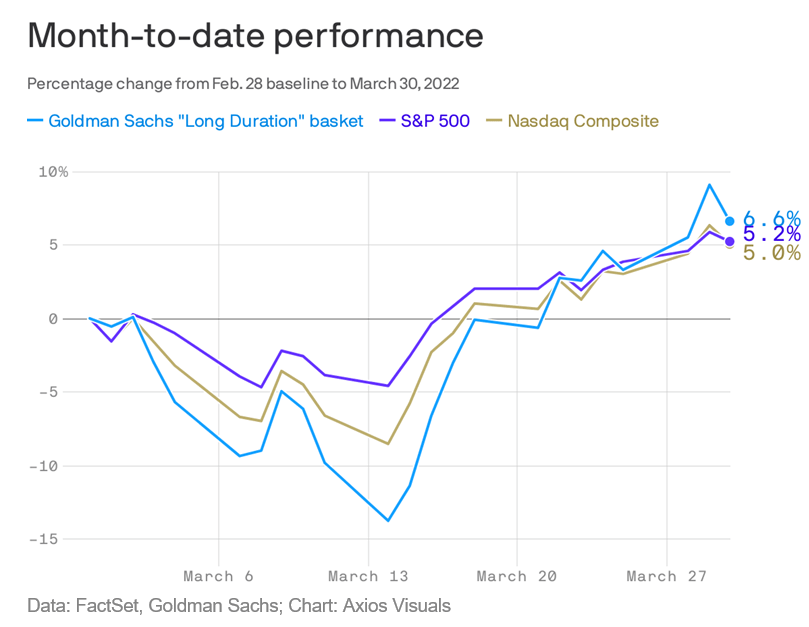

Here’s the month-to-date performance of a couple of baskets of stocks or rather one basket versus two indexes.

First, in light blue is the Goldman Sachs long-duration basket. Those are the growth stocks, the ones that really got hammered at the beginning of this year and really have been struggling since the beginning of last year. The next is the S&P 500, and the last is the Nasdaq. All three are up very substantially this year. In fact, this month, March will probably turn out to be the best month for stocks since October last year. Now that doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense, right? I mean, basically the stock market is saying that we’re not worried about a recession. Why would that be? On the one hand, you’ve got the bond market saying “Through its traditional inversion of the yield curve that we think a recession is coming.” On the other hand, you’ve got the stock market saying, “Nah, we don’t think so.”

Well, here’s what I think. And here’s what very, very few people are actually acknowledging. I think that a lot of stock market investors are betting that the Fed is going to go really hard on interest rate increases in the short term, which will cause a recession, but the recession won’t last forever. Instead, what’s going to happen is that we will get back to the sort of very slow growth under 2% low inflation environment that did so well for stocks, particularly tech stocks in the period after the subprime crisis. For over a decade, we saw great returns. We had an environment where we had a slow economic growth, which made real economy stocks less attractive. We had very low interest rates because we had very low inflation and that led people to pile into tech stocks.

So what I think is happening is that the market is pricing in a recession, but a recession that won’t last very long and will be followed up with low wage growth, low economic activity growth, GDP, but rising profits. And that means that, what they’re actually doing is getting themselves in a position now where they can take advantage of that later. Remember a recession is only two quarters of negative GDP growth, so that could come and go pretty quickly. So instead of thinking about a recession as the end of the world, maybe the way to think about it is that it’s going to be a temporary measure or a temporary correction, which then returns us to something like we had before. Now, will that be the case? Who knows? But the critical thing is that that, I think explains short-term stock price movements. It’s not just animal spirits. It’s, there’s a logical reason to expect that there might be some gains to be had over a longer-term timeframe in the stocks that have been hit the worst over the last year.

And the second thing I want to talk about today is the so-called “wage price spiral.” Now the wage price spiral is essentially the idea that, when you have inflation that becomes baked into people’s expectations, people start to anticipate price rises and to start pricing them in ahead of time, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Consider a company that makes widgets, well, the company that makes widgets employs people, those people demand that their wages be increased by faster than the inflation rate. So they then go to their employers and say, hey, our union contract, next time we want it to be 3% plus one. If the inflation rate is 3%, they want a 4% raise so they get a net increase. In order to cope with that, the widget company then raises its prices by at least that much, which of course, causes inflation, which then feeds back into the prices that its workers pay. So on and so on. So you get a spiral where higher prices lead to higher wage demands, which lead to higher prices, which lead to higher wage demands.

Now, this has been a very popular way of understanding inflation. People like Larry Summers, Mohamed El-Erian, and some of the other inflation hawks, who’ve been critical of the Fed, used this as their explanation because this is what happened in the ‘70s. But here’s the thing… According to the commerce department, the Bureau of Economic Analysis, domestic corporate profits reached $2.8 trillion last year, up from 2.2 trillion in 2020. That’s the largest annual increase since 1976. So, you had an enormous increase in corporate profits. Now, remember corporate profits are the difference between the cost of production and your revenues and everything else. So if profits are rising that much in a period of inflation, that tells you something. That tells you that wages are not pushing into corporate profits. Let’s explore why.

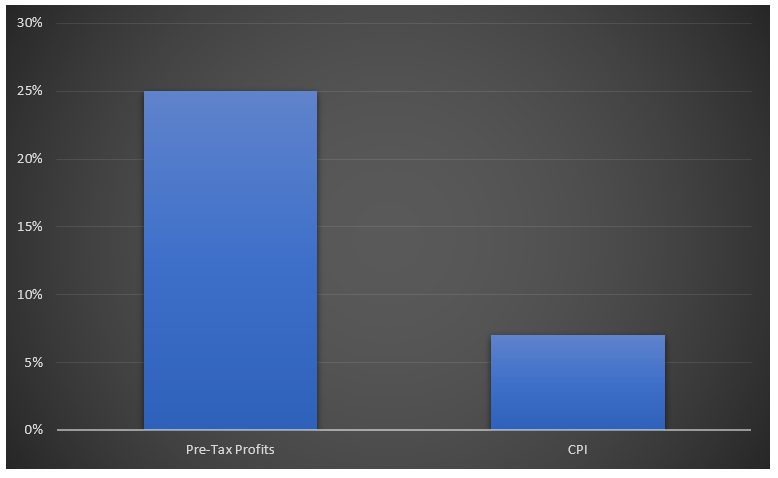

Now, that increase from last year to this year was 25%. In other words, corporate profits rose by 25% from 2020 to 2021, during a period when inflation was supposed to be putting pressure on margins. Now what happened to wages? Remember the wage price spiral is supposed to be wages increase faster than inflation because of employee demands, which then leads companies to raise their prices, which then feeds back into wages. Well, corporate profits rose by 25%, but consumer prices only rose by 7%. Right? Okay. So companies have been using inflation as an excuse for rising prices, but their profits rose by 25%. But the important thing, the critical thing is that the so-called labor share of national income fell back to levels before the pandemic. Here’s a chart that shows that.

You can see from 2020 to 2021, pre-tax profits rose by 25%, consumer price, or CPI, only rose by 7%. Now these companies have been complaining loudly about rising costs for raw materials and labor for most of 2021, but they didn’t suffer for those costs. They raised their prices and then some. Now, you find that if you look at corporate earnings calls, CEOs just can’t stop bragging about jacking up prices and being able to keep their profits soaring and today’s profit data shows that they’re being successful. They are actually not suffering from inflation at all. In fact, they’re doing extremely well and that’s because they have pricing power. Now here’s a chart that shows U.S. pre-tax corporate profits:

And just look at the trendline. I mean, basically since the subprime crisis, corporate profits have been on their way up. They fell during COVID. But look at that, boom, just incredible, doubling since the subprime crisis. Now, here are the profit margins.

We haven’t seen profit margins this big since 1950, folks. So here, you have basically the corporate class in America claiming that inflation is a huge danger because it’s going to drive up wages and squeeze profit margins and slow the economy and cause them to stop investing, but look at how much money they’re making. How could that possibly be the case?

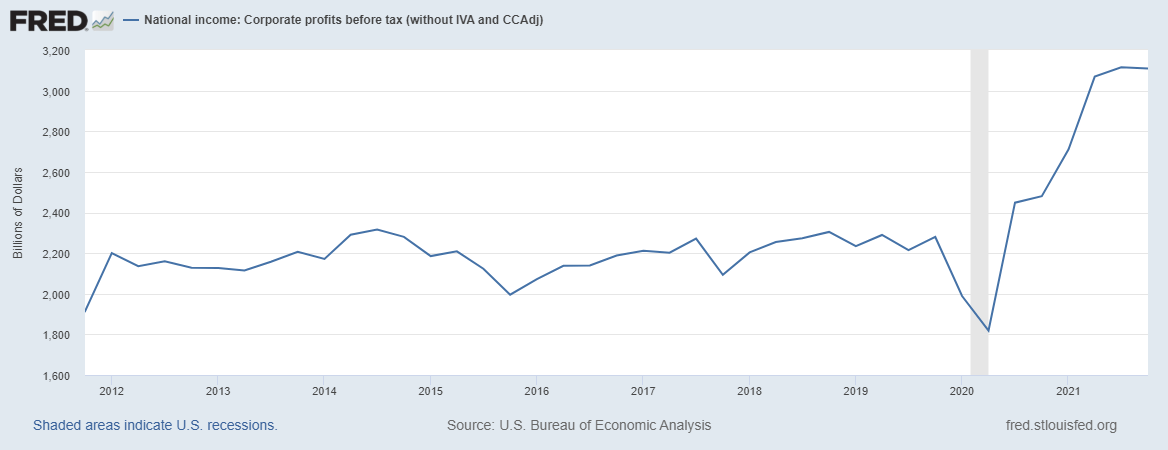

Now, remember that this is not a short-term thing. Here’s corporate profits before tax:

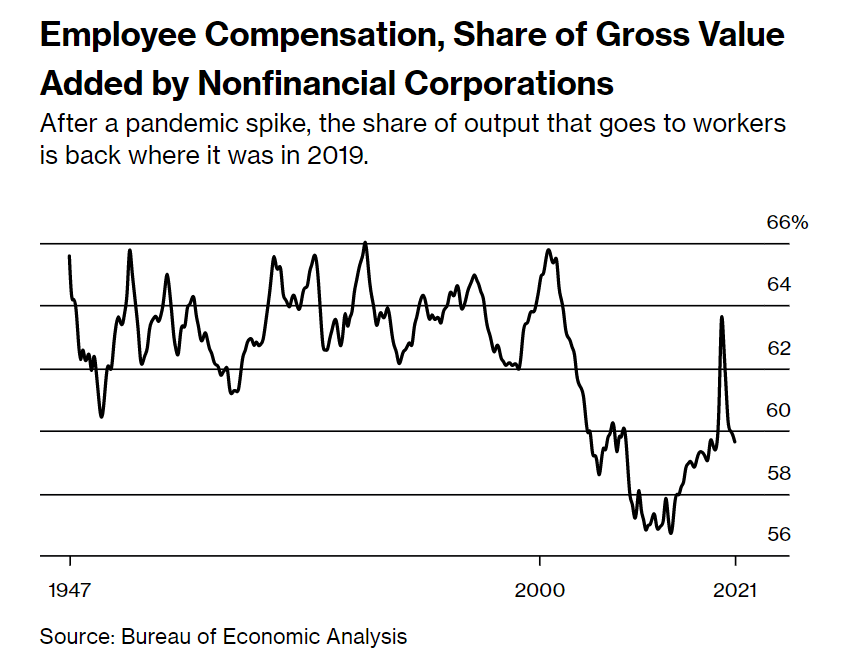

This is a longer-term perspective, actually a shorter-term perspective, but it just shows you that corporate profits before tax were really kind of dawdling along at a fairly straightforward level. They were kind of around $2.2 trillion, but now they have reached just an extraordinary level. I mean, they have almost gone up by 50% since just before the COVID-19 crisis. Now let’s look at what’s happened to employee compensation:

Again, this goes back to 1947, but employee compensation really bounced around between about 62% and 66% of gross value added in the economy. It fell after the dot-com crisis quite dramatically, partly because you were having a lot of the companies that started to do well after the subprime crisis, or sorry, dot-com were technology firms that have lower labor costs. Then it spiked again during COVID, but look, it’s falling back down again.

The bottom line here folks is that people are telling you that inflation is being driven by wage costs, but it’s really ultimately the surge in profits. If you’ve got profits rising that much, eclipsing, far eclipsing rises in work or pay, obviously you’re not having a wage price spiral. It’s not wages that are driving prices higher. It’s that companies are able to raise their prices faster than inflation, thereby contributing to inflation without having that feedback into wages so they can increase their profits. That’s completely inconsistent with a wage price spiral. There’s no other way to put it. So when people start blaming workers for rising prices, forget that. It’s not them.

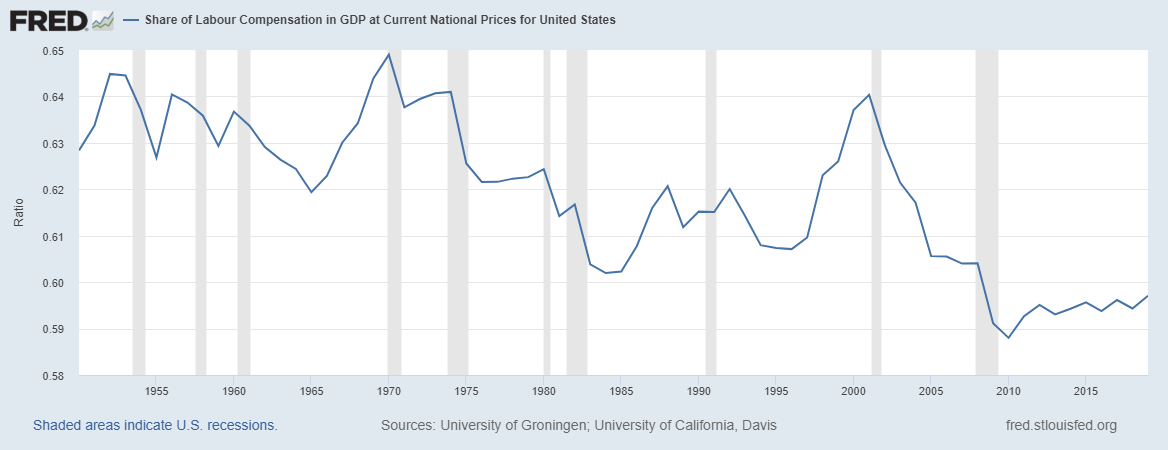

Now, in all post-war economic recoveries, before the dot-com crisis, the lion’s share of the increase in national income after that crisis went to labor compensation rather than corporate profits. It was only after dot-com that we began to see a reversal of that. Here’s a chart that shows that:

Again, going back to World War II, you can see that whenever there’s a recession, laborers share of GDP falls, but then it rises pretty substantially. And look at what happened after dot-com. It stagnated.

Now what’s the big difference? What happened after dot-com? Well, one of the things was that unions had essentially been crushed in the United States, starting in the 1980s with the Reagan Administration. Labor wasn’t in a position to demand higher wages. But the other thing, of course, was the migration of a big chunk of national value-added being created in the technology sector, which has relatively low labor costs. But at this point, what we’re seeing is much, much bigger than that. We’re seeing across the board companies being able to raise their prices without having to raise their wages commensurately.

And so those increases are basically coming at the expenses of low and mid-level workers. Top executives are getting bonuses like you wouldn’t believe. Starbucks’ CEO, Kevin Johnson saw his compensation soar by 39% to $20.4 million from 2020 to 2021, 39% increase in this guy’s compensation just in one year, we talk about wages rising by three to four or 5% in a year and we get freaked out, like that’s a major economic problem, but that’s not the problem. The problem is ultimately that companies are able to raise their prices. And this goes back to something I’ve been talking about for years, which is the lack of competitiveness in the United States economy. Now, I’m not saying that there aren’t businesses that do struggle because of this. Most small businesses, restaurants, any kind of business that has a large labor component, yes, they’re struggling. But the biggest, deepest pocketed companies in the United States are not struggling because of inflation. They are actually achieving the highest profits rate they’ve had since 1950.

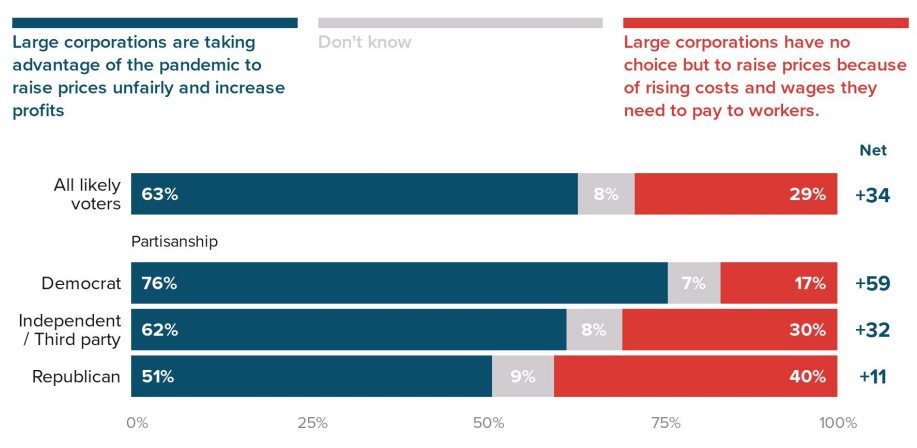

Now, here’s, what’s interesting. You would think that this is an unpopular view that maybe I’m flirting with some kind of socialist or left-wing approach, but here’s a chart that shows that of all political party affiliation in the United States, everybody, including Republicans, a majority of them believe that large corporations are taking advantage of the pandemic to raise prices.

51% of Republicans, 62% of independents, 76% of Democrats, and overall 63% of people believe that large companies are abusing the situation to try to increase their profits by raising prices.

Now, one could say, well, in a free market, you can do what you like. But the problem is that we don’t have a free market. We haven’t had a free market, really pretty much ever because markets are always governed by rules and regulations, laws, and all sorts of things, particularly when it comes to competition policy. And we haven’t had effective competition policy in this country, since the Reagan Administration, when basically Reagan’s people dismantled the competition policy. It’s starting to come back. The Biden Administration has appointed people who have strong views on this and who are committed to reintroducing healthy competition. And that should lead to lower prices.

In the meantime, my message to you is, when somebody blames workers for rising prices and inflation, you refer them to this video. Tell them to go watch it because it’s just simply not true. Corporations and the leaders of corporations are making a money hand over fist and are able to increase their profits and their own pay at a far larger rate than anybody else in the economy. Now, again, you could say, well, that’s the way the ball bounces, but remember, every ballgame has a referee and the referee is the government. And the referees in this case are very, very close to the team on the one side, the side of the bosses.

This is Ted Bauman signing off. I will talk to you again in two weeks; time, because I’m going to be on vacation next week with my daughter who has spring break. We’re going to be taking a trip. Take care.

Kind regards,

Ted Bauman

Editor, The Bauman Letter