Russian sovereign debt default is no longer an “improbable event.”

It’s hard to believe that a few weeks ago Russia was considered to be one of the world’s safest bets for debt. And now, most won’t touch it with a 10-foot pole.

Today Ted Bauman and Clint Lee look past the headline hysteria in this week’s Your Money Matters to talk about a potential time bomb in the global debt markets. Namely, the increasing risk of a massive Russian default and how it could send shock waves through the world financial system.

Click here to watch this week’s video or click on the image below:

Transcript

Ted:

Hello everyone. This is Ted Bauman here, editor of The Bauman Daily, now called Big Picture, Big Profits, and of Bauman Letter. I’m here with Clint Lee, who is our options jockey. We’re here today to talk about what’s going on in the global financial system vis-a-vis Russia, and by extension, Ukraine and Belarus, which also got issues.

Now, I just want to start out with a quote that came from the World Bank’s chief economist, Carmen Reinhart. She says, “When you look at the global financial system, particularly when you look at these situations where you’re looking at default on a country’s bonds, whether they’re government bonds or private sector loans, whatever.” She says, “What I worry about is what I do not see. In other words, what you hear in the headlines is one thing, but what is actually connected to those things that are happening in the headlines. That’s the important thing.”

So this is what we want to talk about today. So one of the things I just might mention is that we have a package that we’ve put together. Basically, it talks about the potential for collapse. If you click on the link in the description below, over the years, I’ve spoken a lot about the potential for a financial collapse, this is a link to a nice presentation on it with an opportunity if you like to join The Bauman Letter and see how we approach these matters.

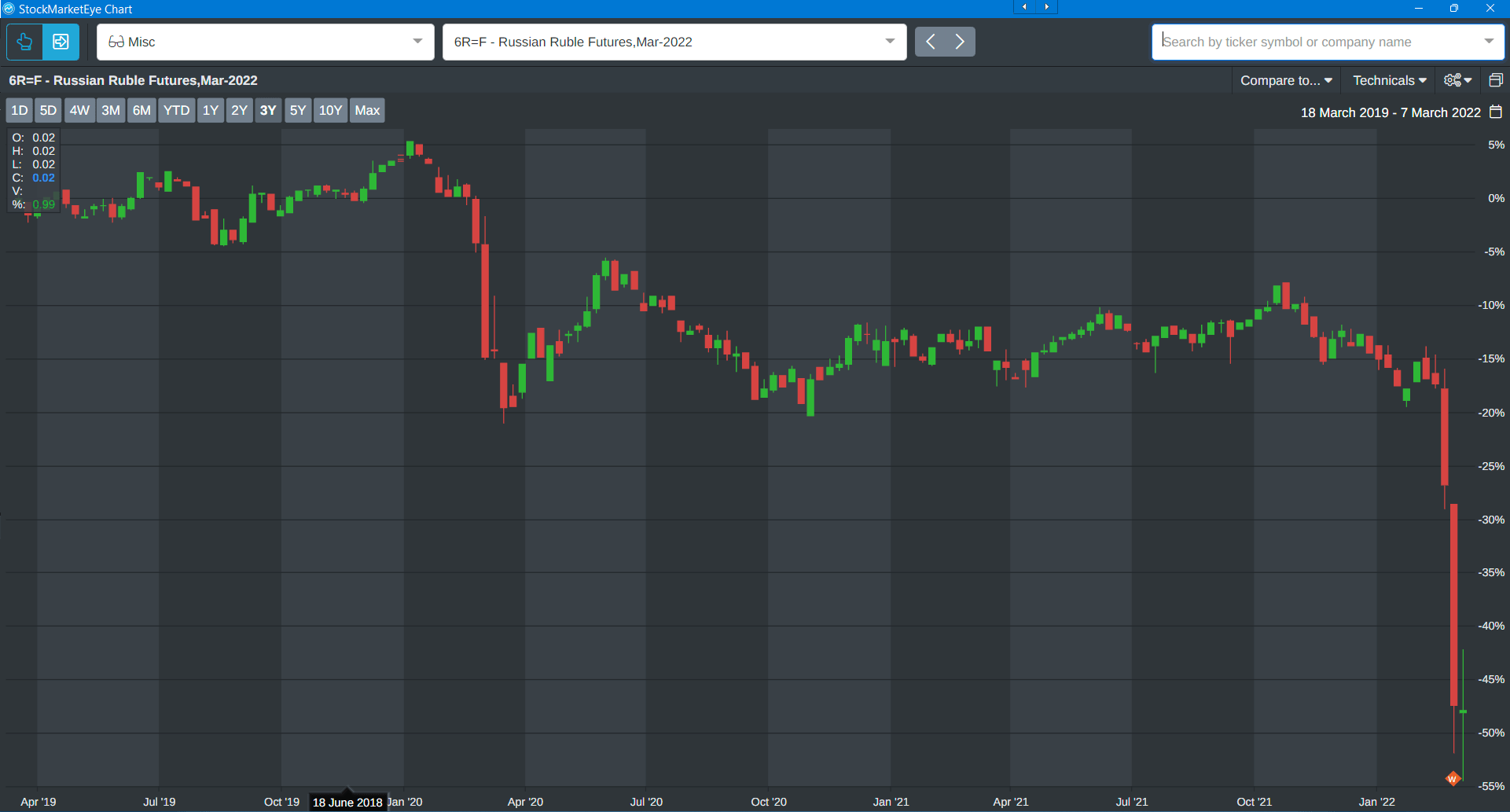

Now, Clint, most people know that the ruble and the Russian stock market have collapsed. Here’s the ruble chart:

Talk about falling off a cliff. There’s a small bounce at the bottom, but not much. Same thing with the Russian stock market. This is ERUS, which is an ETF, which is no longer trading:

Basically, it’s been taken off the market. Now, here’s the weird thing. People are aware of that, but what about Russian debt? Now, up until a few weeks ago, Russia was considered to be one of the world’s safest bets for debt because it’s countries GDP-to-debt ratio was so low.

Russian debt as a portion of total global debt is only about .2%. As a percentage of global GDP, it’s about .5%. As a percentage of Russian GDP, it’s only about 34% which is way lower than, for example, United States, certainly far lower than Japan. Here’s a chart that shows the trend in debt: It just shows that basically the Russian right around 2013, 2014 began trying to reduce their foreign obligations. That was the time when Putin invaded Crimea and annexed it. So clearly they have a strategy to try to do that. Now, where do they stand in terms of external debt? Before I hand over to Clint to explain how this matters, let’s run through some figures.

It just shows that basically the Russian right around 2013, 2014 began trying to reduce their foreign obligations. That was the time when Putin invaded Crimea and annexed it. So clearly they have a strategy to try to do that. Now, where do they stand in terms of external debt? Before I hand over to Clint to explain how this matters, let’s run through some figures.

Russia’s total external liabilities have fallen from about 730 billion in 2014 to about 480 billion today. Now of that, about 135 billion is due to be repaid this year at about 5 billion in the next two years. So there’s a fairly substantial amount of money, not huge by global standards, but that’s a lot of money. Essentially, that is going to be the thing to watch. Now, there’s 117 million payment on U.S. dollar bonds due on March 16th. If that doesn’t get paid after 30 days and they don’t pay it again, that’s a default.

Now, the problem is that Russia has about 630 billion in reserves, but the majority of those are inaccessible, because they’ve been frozen. Russia kept them in foreign banks. Those foreign banks won’t let them have it. Now, there’s a lot of held by foreigners, about 70 billion worth of Russian government bonds. About 20% of their money is held by foreigners. About 28 billion in ruble denominated debt. Russian corporates on the other end have over $100 billion in foreign international bonds. Then there’s foreign banks. They have about $121 billion exposure to Russia, mainly in Europe, which is about 6% of Russia’s total banking assets.

On top of that, you got about 200 billion worth of Russian stocks owned by foreigners, including 68 billion in U.S. Now, critical thing here is that when those things disappear, in other words, when they stop being traded, that subtracts from the world’s liquidity. The total number may not be so big. But the big question is, where are the little chinks in the system that could make them big?

As the Android David said in Ridley Scott’s great movie Prometheus, he says, “Well, big things have small beginnings.” That can happen in the financial system. Clint, tell us why that’s the case. Why do big things sometimes have small beginnings when it comes to the global financial system?

Clint:

Billions here, billions there. What’s it matter, right?

Ted:

Pretty soon it adds up to a lot of money.

Clint:

It does, it does. But I mean, in the grand scheme of things, relative to the global financial system, these aren’t necessarily gargantuan sums, but they are meaningful. To your point, it’s where you start to trigger that snowball effect.

Ted:

Right.

Clint:

I think, one area that you can look at that has an interesting parallel to where we’re at now is a prior Russian debt crisis, what was happening in the late 1990s when Russia in ’98 when they defaulted on debt there, they devalued the ruble, and that mechanism for turning what shouldn’t have been a big impact to the financial system ended up being a big one was through long-term capital management. So a hedge fund that was making some bets at the time. So here’s why it became an issue is because long term capital management, if you’re not familiar with this story, I know at least one book has been written on the topic, it’s very interesting, The Rise and Fall of LTCM.

But what ended up happening was they had about 5 billion in equity for their hedge fund. What they did was they used that $5 billion. They borrowed another 100, over $120 billion on top of that. So they had a debt-to-equity ratio that was basically 25 to one. So they had this huge debt to equity ratio, and then they took those assets, and using derivatives, they ended up controlling over $1 trillion, over $1 trillion in notional value through derivatives, was the size of their bet. So something kind of relatively inconsequential with $5 billion in equity, turning that into over a trillion dollars in bets. So it wasn’t necessarily Russia’s currency devaluation and default at the time that posed an issue. It was just that was kind of the straw that finally started to break the camels back.

Ted:

It’s the leverage in the system, right? I mean, basically.

Clint:

Yeah, it’s that leverage in the system. So that’s why it became an issue. So that’s what you want to look for this time around is what’s sort of the… With the pending or potential for a default, what’s the transmission mechanism? Where can that really start to cascade into something more meaningful? So one market I would look at for that is with credit default swaps or CDS contracts. Now, sounds like a complicated name, but all this is is insurance. Just like how you would buy insurance for your car or your house, you can buy, if you hold a Russian debt security, you can buy insurance to protect against default. Excuse me, I drink real quick. Just like you can buy-

Ted:

Vodka, perhaps?

Clint:

Yeah, pretty much. Yeah. Just like you can buy, if you buy a car insurance, you pay a premium to the insurance company. The insurance company in turn, if you get into an accident, they’re going to make a payout. It’s the same thing with these debt security. So if you hold a Russian debt security and you can buy this contract, you make these premium payments, but in turn, if there’s a default, you lose money, there can be a payout. The big concern now, and this kind of goes back to the financial prices too, is who is writing these insurance contracts. Who’s left holding the bag in the unlikely… No one saw the financial crisis coming, or a few did. Who saw this coming? Who’s been out there writing a bunch of insurance contracts to ensure against a Russian default?

Ted:

So AIG, for example, was the one. I mean, that was really what sank them, wasn’t it? AIG.

Clint:

AIG. Any number of major investment banks were getting into trouble because they’ve been writing all these contracts. All of a sudden there’s a default, so now they got to pay out.

Ted:

So how much is it starting to cost to buy this insurance? I know you have some stats on that.

Clint:

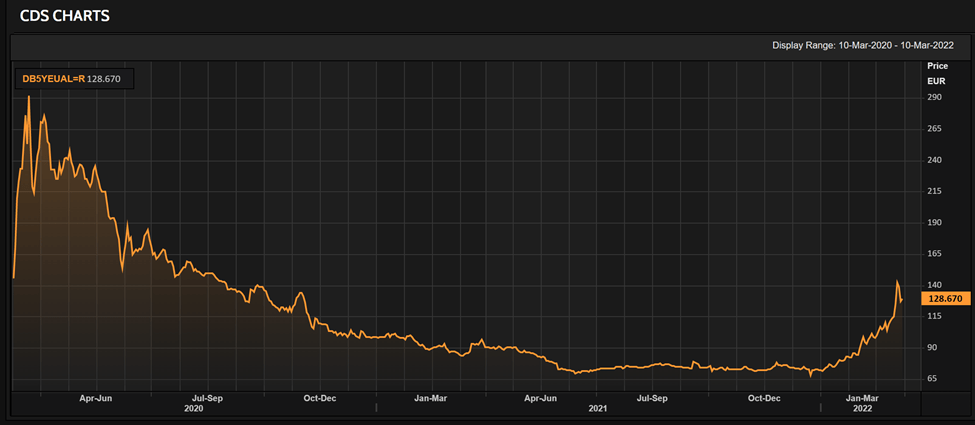

Yeah. I’ve got some stats on it. So here’s a chart of a cost of one of those contracts on Russian sovereign debt, on government debt going back a couple years.

You can see, I mean, just in the last few months, I mean, this has gone from 200 basis points or about 2% to 1,651 basis points. So it’s just absolutely shot higher, which you would expect with what’s unfolded here in the last month. But just as it pertains, as it relates to that, once again, you don’t know where the exposure’s at of who’s been writing these things.

So here’s a chart of Deutsche Bank and the price to ensure against default from Deutsche Bank.

So this is their credit default swap. It’s basically doubled over the last month or so. It’s gone from 65 basis points to 120 basis point. So you’re seeing a jump in the cost insured against default for Deutsche Bank. You’re seeing this actually with a lot of other European banks as well, because once again, it’s not clear right now. It’s hard to get this information of who might have exposure to this snowballing effect, if this starts to pick up the pace.

Ted:

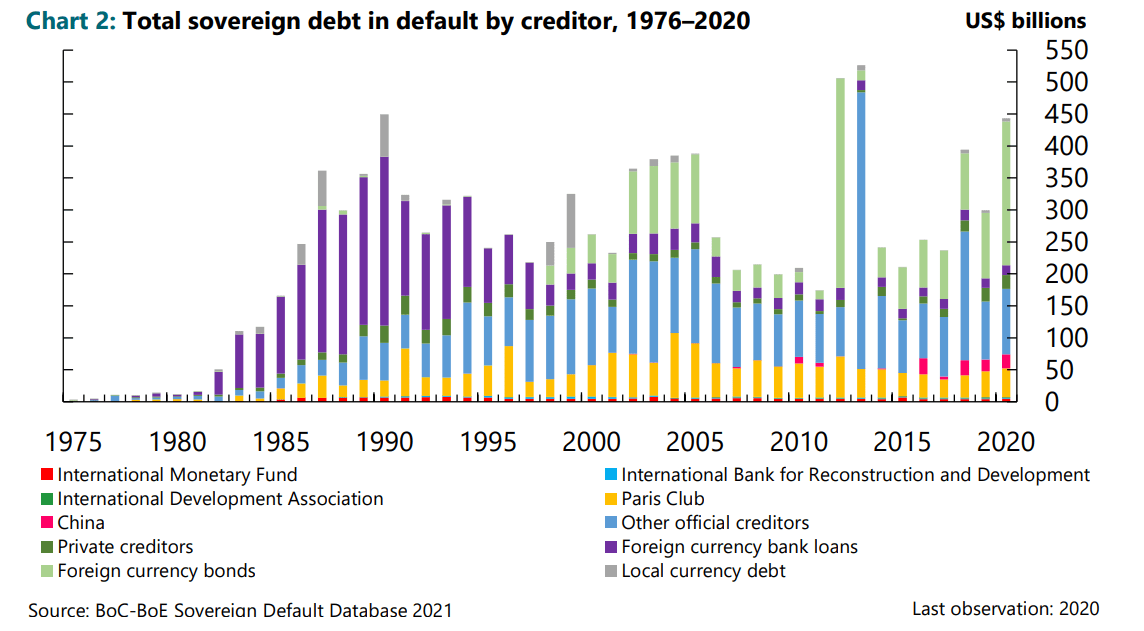

Well, clearly the fact that Deutsche is seeing an increase in its own CDS rates means that they could be. Now, we’ll talk about that in a moment, but I just want to show a chart that shows the evolution of sovereign foreign debt defaults.

Now, over the years, it’s happened a lot. It used to small countries. It used to be Latin American debt crisis. There were African issues. But that has become much more homogenized. It’s spread way across many different parts of the system. The biggest problem is that the more you have in default, the more liquidity that’s being withdrawn from the system, the more risk there are to counterparties.

Now, let’s talk about who is exposed in Russia. Well, here’s Larry Fink from BlackRock:

And the reason he looks like this is because they reckon they’ve probably lost about $17 billion on Russian equities as a result of the collapse. Now, that is not end of the world for BlackRock, but 17 billion is not nothing. I mean, it’s a lot of money and that’s just the equities market.

Now, let’s look at some of the financial markets. UniCredit in Italy is exposed to the tune of $8 billion. Deutsche itself has $1.55 billion exposure, and that’s only 0.3% of its loan book and look what’s happening to its CDS. So imagine what’s happening to UniCredit or BNP Paribas in France, a 3 billion exposure to Russia. Deutsche Bank, basically all of these banks have exposure to Russia that are actually larger than Deutsche’s and yet so they’re going to be paying more for credit default swap.

Clint:

A lot of things that you’re highlighting too is just what they might hold in terms of a loan exposure.

Ted:

Right.

Clint:

Or equity security. What you don’t know is if they’re, behind the scenes, writing derivative type contracts. It’s those unknown exposures that is the cost for concern, especially,

Ted:

Right. For example, PIMCO, one of the great trading houses. It was also involved in LTCM. It had big issues during the 2008 crisis. Apparently, they have $2.6 billion exposure to Russia, but 1.1 billion of that is credit default swaps. Now, again, that’s not huge in relation to their biggest, to the amount of money they have under management, but that could still be a problem. But there’s a unique problem with Russian CDS. Could you tell us a little bit about that? This is something I find fascinating a lot of people are not aware of.

Clint:

Well, there’s just a lot of nuances and technicalities into what constitutes a default.

Ted:

So basically, what happens is that when you write a CDS, you’re saying, “We’ll insure this. If the bond goes into default, then we will auction it on the market, and whatever we can get for that, to the extent that that’s below what you were owed, we will pay you the difference.” In other words, you will get your full amount, but you have to be able to auction the CDS in order to be able to make the CDS contract work. Now, the problem in Russia, or with Russian bonds, is that if these things are embargoed and nobody can trade in them, you can’t auction them, which means that they fall into the category of being non-tradable assets, which means that they are no longer eligible to be covered by CDS.

So the big problem right now is that nobody knows how this is going to unfold. Here’s a chart that shows what’s happened to European banking.

This is an ETF called EUFN. It’s European Financials. We actually bought it for our Bauman Letter, what we call our big picture portfolio, which is basically short term trades and exchange traded funds. Because we were bullish on European Financials. But look what’s happened. Essentially, all this bank’s exposure, the European bank’s exposure to Russia, as small as it is, it panics the system. So what’s the ordinary investor to do in a situation like this, Clint?

Clint:

Know where your exposures are.

Ted:

Right.

Clint:

I would become familiar with things like credit default swaps for the underlying stocks that you own and monitor how those are trending, because there’s a lot of smart investors that are dealing in these things. If they’re pushing up that cost to ensure against default, somebody somewhere knows something.

Ted:

Yes, yes, yes.

Clint:

So that’s one thing to monitor. Just really quick, I was going to mention too, just around the… You’re pointing out the settlement issues with the credit default swaps and how they get auctioned. The one thing I was going to point out there is that also with the sanctions that have been levied against Russia, if that interferes with any of the terms of how these contracts work. So that’s something to be aware of as well, part of what’s messing up the system here.

Ted:

Right. So I mean, everybody knows how insurance companies operate. They sell you insurance, and then they do everything they can to avoid paying out on it. So what’s happening in the background here, folks, is that all of these bonds, to the extent that they are being… Repayment on the bonds is stopped because of sanctions, the CDS people who issued these contracts can say, “Well, we can’t insure that because that’s not a covered event and so therefore we’re not going to pay.” So the question is, what hedge funds, what banks were relying on CDS insurance to be able to cover them and who’s not going to get it?

So that’s what you want to look at, folks. You can get information on CDS from various places, but we’re going to keep an eye on this. Because if we do see any particular institutions that look like they’re exposed, we’ll want to alert you, particularly if you hold stocks. But right now, we don’t see an immediate problem with the financial system, but you never know.

One bright possibility, which is very interesting, is that just like the U.S. has done with Afghanistan foreign funds, you remember earlier this year, the Biden administration said they were going to confiscate them and pay them to others, that could happen here. I mean, you could end up with so-called vulture funds buying Russian debt on the expectation that eventually the U.S. and the EU are going to use Russia’s frozen money to pay off those debts. They could make a lot of money. So there’s lots of possibilities here, both on the good and the bad side. We here at Big Picture, Big Profits will keep an eye on them for you. Anyway, we’ll talk to you next week. Have a good one.

Good investing,

Angela Jirau

Publisher, The Bauman Letter