One!…

Two!…

If you are a parent or are the child of parents who employed the dreaded three count, you never want to experience “Three!”

The arrival of “Three!” meant either a quick slap on the rear or a time-out session in your room.

In order for the count to be effective and stop Little Johnny from climbing the tree and return to the house for dinner, “Three!” needs to be a credible threat. The word must be associated with a previous repercussion for disobedience, or the count will simply fall on deaf ears.

Its effectiveness lies in the mutual understanding of the meaning of “Three!” between child and parent. It is this common understanding that shapes behavior and renders the signal effective.

In short, “Three!” must always be a credible threat. The more you use it without consequence, the less effective it becomes.

Over four decades, the Federal Reserve has played (and won) the game of “Three!” with investors. Whenever it started the countdown, markets bent to its bidding.

In winning this game, the Fed smoothed out the business cycle, tripled the size of the U.S. economy and avoided prolonged recessions.

But this game is getting old. The Fed’s three count must now come with a larger set of consequences — zero interest rates and quantitative easing.

The Great Moderation

In 2002, economists James Stock and Mark Watson published a noteworthy paper titled: “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?”

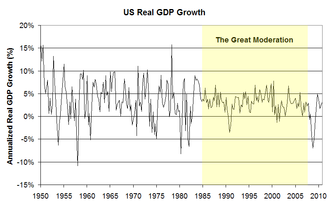

In it, they proposed the idea of the “Great Moderation”: a period of reduced economic volatility that started in the 1980s.

Through increased central bank interventions, the Fed was able to minimize the volatility of major economic variables such as real gross domestic product (GDP), industrial production and monthly payroll employment.

For instance, take a look at this chart of historical GDP volatility:

The Great Moderation started with the 1979 appointment of Paul Volcker as chairman of the Fed.

Volcker was a master of the three count, and some economists believe his actions saved our country.

At Volcker’s first Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting in 1979, the fed funds rate stood at 11.2%, and 12% inflation was crippling the U.S. economy.

Volcker took a no-holds-barred approach to stomping out inflation. In the span of his first two years, he doubled the fed funds rate to a whopping 20% by June 1981! That’s the equivalent of bringing a bazooka to a knife fight.

After a decade of economically stifling inflation, it finally peaked at 13.5% in early 1981. Volcker’s moves saw inflation fall to 3.2% by 1983.

Volcker earned his credibility. His do-what-it-takes approach made investors believe that inflation would disappear through an all-or-nothing policy of aggressive interest-rate raises.

Remember, the Fed can’t change the rate of inflation, but it can take steps to cause a behavioral change in consumers and investors. It’s simply performing a kabuki dance and hoping that we are all paying attention.

The Fed’s power only exists in the market’s perception of the Fed’s power — the three count.

When Volcker’s Fed raised interest rates to 20%, he meant business. Investors believed he would do anything possible to beat inflation, and this changed consumer expectations and behavior, leading to a downward spiral in inflation.

Volcker was heralded as the Muhammad Ali of inflation-fighting central bankers, and the Fed earned its credibility in the hearts and minds of investors.

He paved the way for the three counts of his predecessors to be taken seriously.

The Three Count Gets Stale

Every parent knows: If you use the three count too often without consequence, it loses its magical powers.

And when that count is used to deter one behavior but then reapplied to enforce the same behavior you were most recently trying to deter … your credibility is immediately questioned.

This is the dilemma the Fed now finds itself in.

Three months ago, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell three-counted the stock market rally.

The Fed was concerned that a tight labor market would lead to inflation above its 2% mandate. So it forecasted between one and three rate hikes in 2019.

But that wasn’t enough. It also added hawkish rhetoric about letting its $4 trillion balance sheet run off faster than anyone expected. These are the government, mortgage and corporate bond assets the Fed purchased during three rounds of quantitative easing.

Investors’ response was swift, and likely not anticipated. The stock market cratered 14% in December, which left it in bear market territory, down 20% from its all-time high.

It was as if the Fed three-counted Little Johnny out of the tree, but instead of climbing down, he tried to jump.

The Fed realized the havoc its rhetoric hath wrought, and quickly changed its tune.

On Wednesday, it confirmed what the market has known for months — that Powell is now a “yes-man,” and the Fed would remain on hold for the foreseeable future.

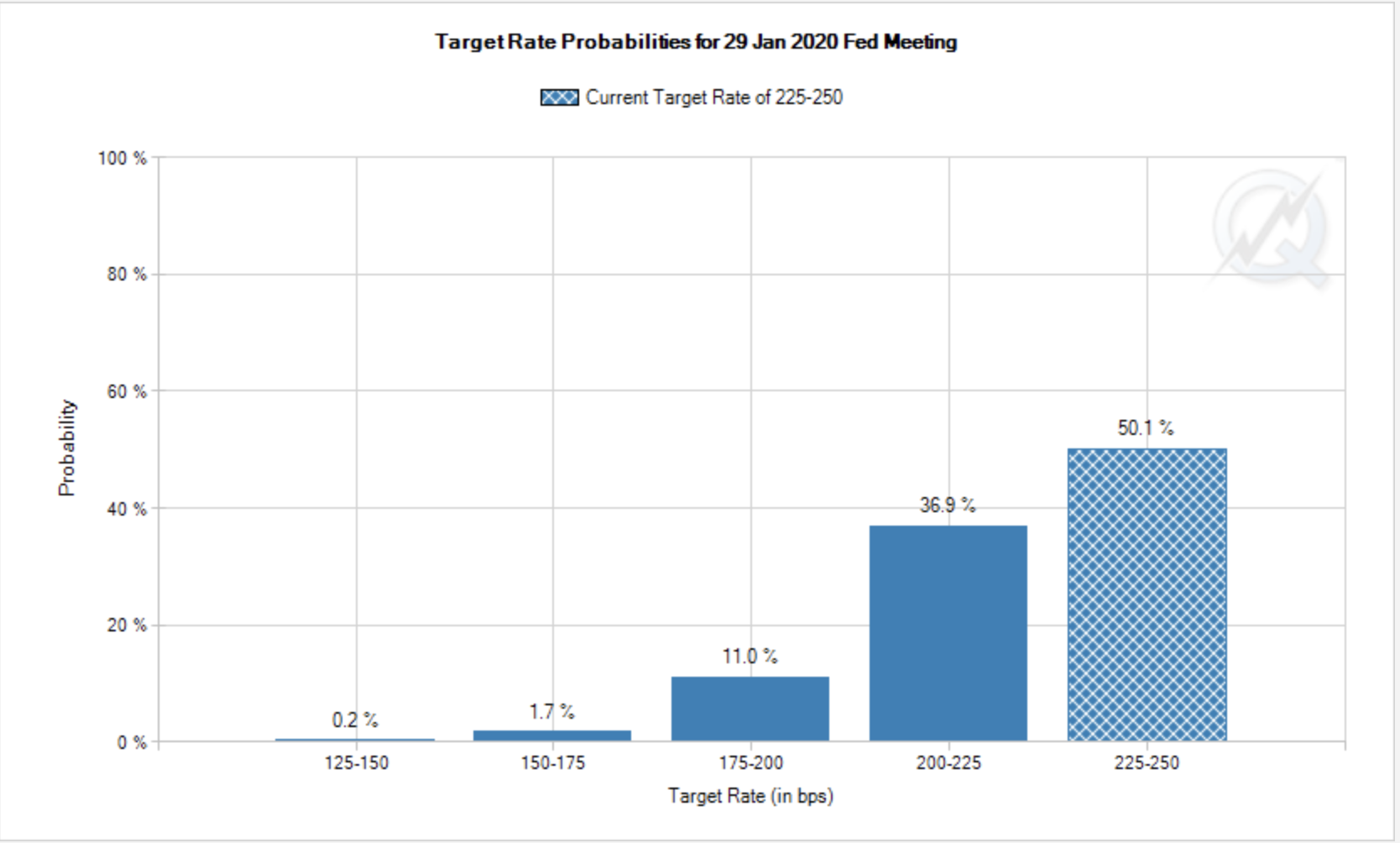

The fed funds futures for January 2020 are now pricing in zero rate hikes for the next year, and a 50/50 chance of rate cuts:

Before the FOMC meeting this week, the market was pricing in a 25% chance of rate cuts. In December, we were looking at higher odds of rate increases.

Now, the market is actually forecasting an 11% chance of a 50-basis-point cut by January 2020.

This is a sudden about-face by the Fed and a sign that the market believes the Fed will keep monetary policy easy for at least the next nine months.

The odds of lower rates should keep stocks rallying this year, provided the economic data doesn’t fall off a cliff or the Chinese trade war fears worsen.

Investors will continue paying attention to the Fed’s three count … until it stops working.

Regards,

Ian King

Editor, Crypto Profit Trader