In a Bauman Daily article a few weeks back, I talked about the danger of assuming that the future would be just like the present.

The human brain is wired to do exactly that. Our survival as a species depends on our ability to learn from experience. And recent experience leaves the strongest memories.

But this so-called “continuity bias” is dangerous for investors — people who buy assets for the long haul.

Let’s say that you believe, as I do, that the modern economy is in the middle of a long-term trend of secular growth. That should be good for stocks. But which ones? Getting that answer wrong can be costly.

Consider the 1920s, the so-called “roaring” decade.

In 1921, most people knew that the next big thing was the automobile. Farsighted investors put their money there. But by the end of the decade, industries that hadn’t even existed in that year were poised for even bigger gains.

At what point would you have switched some of your money into the companies of tomorrow like the Radio Corporation of America, General Electric or Bell Laboratories?

Analysts are increasingly speculating that we could be on the cusp of another transition to new growth leaders.

Knowing when to make the switch could mean all the difference to your portfolio.

Are YOU Ready for Risk?

(Click here to view larger image.)

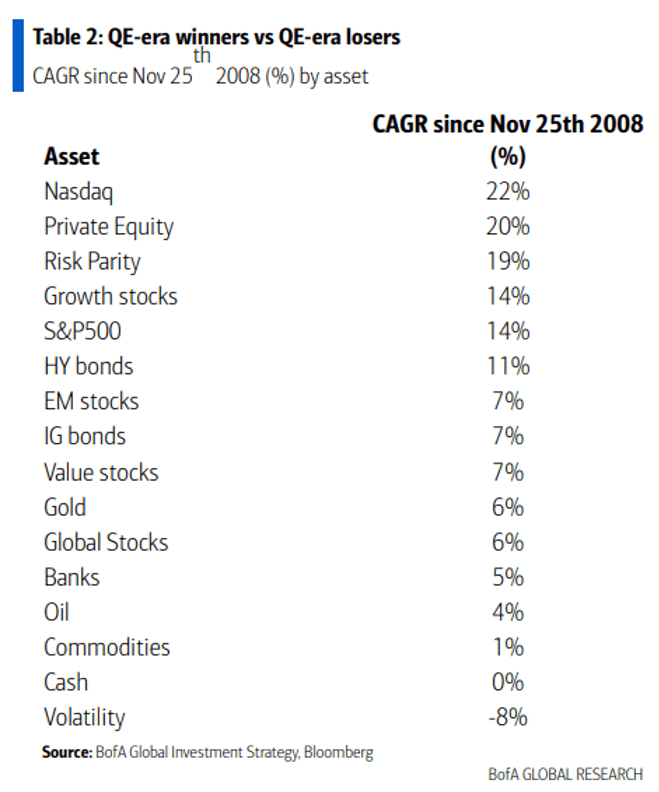

This table comes from the Bank of America’s global research division. It lists the compound annual growth rate of 15 asset categories, plus volatility, since the stock market collapse of November 25, 2008.

The technology-heavy Nasdaq leads the way. That’s no surprise.

Growth stocks are also near the top. Again, no news there.

By contrast, commodities, financials, value stocks and non-U.S. equities performed poorly.

But the third best-performing asset category is one many investors have never heard of: “risk parity.”

It’s one you should be thinking about.

Risk parity is an investment strategy that balances a portfolio according to risk rather than return. Each asset contributes the same amount to the overall risk of the portfolio. Higher-risk assets are held in smaller proportions than lower-risk assets.

For example, a risk parity strategy would limit its holdings of an exchange-traded fund like the ARK Innovation ETF (NYSE: ARKK) because it’s highly volatile compared to the market average. The fact that it’s packed with “next big thing” companies and has made a 450% return in the last five years wouldn’t matter.

The problem is that far too many investors have over-weighted their own portfolios based on recent returns rather than risk.

If the distribution of stock market gains shifts, where will they be?

An Artificial Market on Borrowed Time

Current discussions about risk focus on things like inflation, interest rates, U.S. debt default, taxation and geopolitics.

But the number one risk right now is the controlled demolition of the emergency scaffolding erected around the global economy after the great financial crisis and strengthened during the COVID-19 crisis.

That scaffolding is called qualitative easing, or QE. It’s been around so long that many investors take it for granted.

They could be in trouble if they don’t start factoring in the risk of a world without QE.

QE is all about “easing financial conditions.” It involves the Federal Reserve buying government bonds and other securities from big financial institutions in exchange for cash.

Over the last decade, that’s done four things:

- It increased liquidity (cash) in the global financial system. Banks and other lenders have more to lend. That pushes down interest rates and keeps the pressure off debtors. This aspect of QE was so successful that yields on even the junkiest of junk bonds are ridiculously low. In market terms, QE has “mispriced” the risk of those bonds … they appear safer than they actually are.

- By taking so many Treasury bonds off the market every month, QE artificially reduces their supply. That pushes up their price and reduces their yield. The result has been an unprecedented decade-long bull market in both bonds and stocks. That’s not supposed to happen. It has led investors to become over-allocated to riskier equities at the expense of bonds.

- Low interest rates have allowed companies with huge cash flows, like Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Alphabet, to expand much faster than their smaller competitors. It’s often overlooked, but the incredible revenue growth and expanding margins of these mega-cap companies in the last decade is a direct result of QE.

- Low interest rates have made the future cash flows of companies in “next big thing” sectors more attractive than they would be otherwise. Throw in lots of liquidity to buy their shares, and those companies have seen unprecedented gains in a short period.

The bottom line is that QE has produced a set of investment shifts that would not have happened otherwise … or at least not at that scale. Those shifts are based on “mispricing” of assets compared to an environment without QE.

And now, the Federal Reserve is intent on dismantling QE.

What happens to that pattern of asset mispricing?

From QE-Winners to QE-Losers

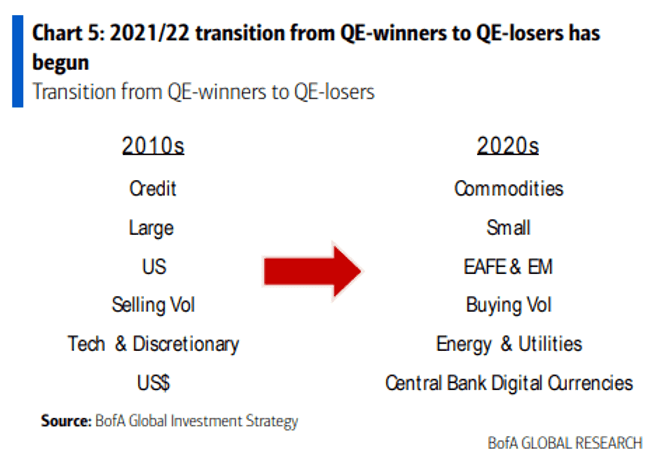

The folks at Bank of America global investing believe the answer to that question is already emerging. They expressed it in this chart:

QE helped expand credit markets, allowed big companies to get bigger, rewarded investors in speculative technology, goosed the U.S. stock market and made it less volatile. All of this is ultimately based on the biggest “mispricing” of all: money itself.

But there’s a limit to that sort of artificial mispricing, and it looks like the market has reached it. For example, during 2021, investors realized that it would take Tesla (Nasdaq: TSLA) 1,300 years to generate enough cash flow to justify its share price. Or that it would take over 20 years of revenue, at no cost of production, to do the same for Zoom (Nasdaq: ZM).

Bank of America’s view is that the decline in stocks of QE-era darlings like Tesla and Zoom means that we have reached “peak QE.”

The fact that it is happening before the Fed begins to taper its bond purchases suggests the scale of what could be to come as the entire QE framework is dismantled.

That’s why for the rest of this decade, they are bullish on commodities, small caps, non-U.S. equities, energy (especially green!) and utilities (especially green utilities!). They also anticipate much higher volatility.

Add it all together, and this means that if your portfolio is over-weighted towards the last decade’s winners, your “risk parity” for the next decade could be dangerously out of kilter.

That’s precisely why, for the last two quarters, I’ve advised readers of my Bauman Letter to put their money into companies on the right-hand side of the chart above!

That’s where our newest pick fits. To find out how to get a copy of the latest edition of The Bauman Letter, click here.

Kind regards,

Ted Bauman

Editor, The Bauman Letter