My first thought was an unspoken prayer: Dear God, not again!

My reaction to the terrible news that a gunman had fired on a group of Republican members of Congress, wounding six, brought me right back to March 1, 1954, at 2:30 in the afternoon, the moment when four Puerto Rican nationalists in the visitors’ gallery fired 30 rounds down into the House of Representatives chamber, hitting five members.

I was a 15-year-old House page. I saw a wounded congressman fall at my feet, and I helped my fellow pages carry the injured to ambulances by the Capitol steps. Later, as a member of the House of Representatives myself, I received death threats serious enough to involve the FBI.

The brutal assault Wednesday was a deliberate attempt to assassinate Republican House members, for whom the shooter repeatedly had expressed hatred, as he did for President Donald Trump.

Immediately, pundits warned that we should remain calm and not politicize the event. But as one observer said: How do you depoliticize the attempted assassination of a dugout full of Republican lawmakers?

A Call to Heal Wounds

On January 10, 2011, I wrote: “As a human being and an American, I join with the great majority praying for U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords’ full and speedy recover — for all those injured in this senseless madness.” A nonpolitical but deranged mental patient had shot Giffords, who survived; six others died.

In response, on January 13, 2011, President Barack Obama spoke in Tucson, Arizona, saying that American discourse had become sharply polarized, with too many people blaming “those who think differently.” He said that Americans must talk with each other in ways that heal and not wound. Don’t use this tragedy, he advised, “as one more occasion to turn on one another.” He might have made that speech today.

Obama’s advice in 2011 did not stop The New York Times from screaming anti-conservative invective. Its lead editorial offered this irrational indictment: “It is legitimate to hold Republicans and particularly their most virulent supporters in the media responsible for the gale of anger that has produced the vast majority of these threats, setting the nation on edge.”

So, now, should legitimate blame rest with the “impeach Trump” crowd, the talking heads of the biased media and sick comedians who imitate beheading the president? Did they create a poisoned national atmosphere in which GOP lawmakers are fair game for an enraged Democrat’s bullets?

A Divided People

Ironically, Wednesday’s shooting occurred during a practice session for the annual congressional charity baseball game, a festive bipartisan event staged annually since 1909. The annual game is one of the few surviving Capitol Hill traditions that bring partisans together for a good common cause.

Expect a torrent of biased opinions that refashion this horrific attack to suit the agendas of the political extremes. Yet, we are warned not to raise our voices, to be calm and reasonable. It does no service to the victims of such violence, nor to our country’s future peace and welfare, to remain silent and ignore the causes that fan the flames of such madness.

Reasonable Americans realize today that in Congress, the White House, the news media, on college campuses — all over America — there is rancor and bitterness that make reasonable compromise impossible and prevent solutions.

This horrible act by an angered partisan must be rejected, but the suffering he caused should not be trivialized by those seeking advantage from a bloody tragedy.

I live in the hope that a free America will survive, but I do wonder about the endurance of the republic the Founders gave us at such great cost — which more than a million souls have died defending in all our wars.

Politico Magazine summarized the violent nature of American politics:

Political violence runs through the American story like a razor slash. Gunplay has harvested four presidents — Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley and John Kennedy — and depending on how you count, assassins have taken target practice on another eight or nine sitting presidents and presidential candidates.

On my 31st birthday, April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. My wife and small children lived through days of riots, fires, curfew and armed U.S. Army occupation of our Washington, D.C., neighborhood.

That same night in Indianapolis, U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, a candidate for president, addressed King’s death, a sad occasion which, he said, suggested stark alternatives for individuals and for America.

You can be filled with bitterness, with hatred and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization […] filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort […] to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand compassion and love.

Sixty-two days later, on June 5, 1968, Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

Sixty-two days later, on June 5, 1968, Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

The choice of revenge or reunion is ours again today.

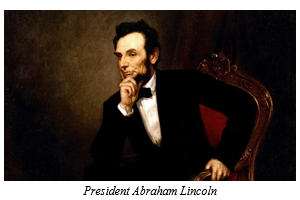

In 1861, the soon to be martyred President Abraham Lincoln gave us the course to follow.

On the eve of the Civil War, in his first inaugural address, he voiced this heartfelt plea:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Yours for liberty,

Bob Bauman, JD

Chairman, Freedom Alliance