Last week, I wrote about the pain of losses. We have mathematical proof showing that painful feelings of losses cloud our decisions.

If we overcome that fear of pain, we could achieve better results as traders.

But shrinking from the pain of losses is just one way our emotions can negatively influence our portfolio.

Behavioral finance experts have identified dozens of ways we can go wrong in deciding when to buy and sell. Their data shows that we all have biases that drive mistakes.

Let’s take a look at three major biases you could be carrying that could drag down your portfolio…

Are These 3 Biases Killing Your Profits?

Let’s start with salience. This is an important bias to understand. It means we tend to focus on the wrong things.

As investors, we may overweight the latest news. For example, let’s say we see that inflation rose 0.1% last month. That’s a big decline from six months ago. We expect inflation to stay low and start buying stocks aggressively.

The latest report is salient information. If only we were to dig deeper, we would see that home prices are reported with a lag. Just that one factor might drive inflation to 0.3% next month.

This requires a detailed analysis, but many investors don’t dig deep. They take a single data point and run with that.

Research shows we’re comfortable doing that. It’s easy to make decisions without detailed analysis.

It’s also easy to do what everyone else is doing. If we find that inflation is set to rise while everyone believes it will fall, we are uncomfortable. That’s the herding instinct, our natural desire to be part of the in-crowd. For investors, herding means that instead of going against the crowd, we ignore data and follow our friends.

The tendency to ignore data is especially common when the data contradicts what we want to believe. This is known as the anchoring bias.

Sometimes we anchor on previous prices. It’s common to anchor on recent highs. We expect prices to reach those highs again. Low prices mean we’re getting a bargain.

We overlook the fact that lower prices could mean sales are falling. Or profit margins are shrinking. More often than not, low prices mean bad news rather than a chance to buy at a bargain.

Anchoring means investors ignore the latest information. They focus on something that confirms what they want to believe.

While there are research papers on these biases (and many others) the real world isn’t as precise as academic research. Biases often interact and amplify each other, and GameStop (NYSE: GME) is a good example of that happening in the real world…

The Perfect Storm for Biases Running Amok

GameStop hit the news in January 2021. Traders on a Reddit message board started buying. They wanted to teach Wall Street short traders a lesson or something.

Their buying pushed the price up. The hedge fund they targeted did suffer losses. Eventually, the manager shut the fund down. Poor guy. He’s probably thinking about the lessons he learned in his $44 million Miami home.

As individuals piled into the GME trade, they were driven by the salient information that Redditors had found a way to make millions. In reality, few actually made large profits in the trade. There are rumors that some of the biggest hedge funds did profit from the trading frenzy. That’s probably true.

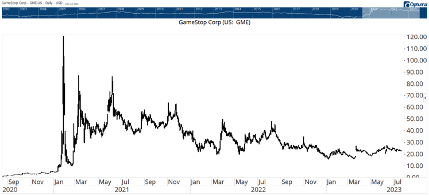

Much of the buying resulted from erroneous anchors. Many investors anchor on information they like to believe. They bought GameStop at $60 a share in early 2021. They anchored on the recent high of $120 a share. They were getting a 50% discount in their mind.

They believed the stock would double — or more. The argument was that it was $120 at one time, so it would surely reach that level again.

Buying also allowed investors to be part of the herd. Millions of individuals were buying. They were online congratulating each other for buying. But unfortunately, many never profited.

The chart below shows that GME never reached its old high. Although the stock has been volatile, it’s generally been in a downtrend for more than two years.

GME Never Returns to Old Highs

Rational investors avoided GME. The company was (and still is) losing money. Management described the company’s situation in the 2022 annual report:

At the start of 2021, GameStop had burdensome debt, dwindling cash, outdated systems and technology and no meaningful stockholders in the boardroom. The company was in distress and had an uncertain future.

None of this was a secret at the time. Everyone could see that the company was in trouble. The only reason the stock went up was because traders believed they could “stick it” to Wall Street by buying. And that’s what drove the buying.

If you bought GME in early 2021, you were part of the group (herding). You believed the price could top $100 a share because it had done that before (anchoring). And it was something you kept seeing in the news (salience).

In hindsight, it was a trifecta of errors that led many to losses during the GME frenzy.

Herding, anchoring and salience biases will almost always lead to errors.

Recognizing that you can make these errors is the first step toward avoiding them. It’s a step that could help you avoid thousands of dollars in losses in the future.

Regards, Michael CarrEditor, Precision Profits

Michael CarrEditor, Precision Profits

Add Recency and Availability Biases to the List

For decades, the prevailing wisdom on Wall Street was that the market was “efficient,” and that investors rationally analyzed all available data and priced stocks appropriately.

Of course, that’s absurd. Study after study proved the efficient market hypothesis wrong. Our own Adam O’Dell incorporated some of those “anomalies” into his market-beating Stock Power Ratings system.

But it took two nonfinancial psychologists to explain why the market isn’t efficient.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky effectively rewrote the finance and economic textbooks with their study of behavioral finance. Actually, I can’t say that they “studied” behavioral finance. They invented it.

Mike mentioned salience, herding and anchoring as cognitive biases that can lead us to make poor decisions. To these, I would add two more closely related biases: recency and availability.

What Is Recency Bias?

Recency bias is exactly what it sounds like. It’s the tendency to put undue weight or importance on recent information when making decisions about the future.

In plain English, it’s the mistake of assuming the future is going to look like the recent past.

You don’t have to be a market wizard to understand why that would be dangerous. The market rips higher … until it doesn’t. Or large caps outperform small caps … until they don’t. Or a short-squeezed meme stock is a “can’t lose” investment … right until it loses.

You get the idea!

What Is Availability Bias?

Availability bias is similar. It’s the tendency to make decisions based on examples that come to mind, often because the examples are extreme or traumatic.

For example: Because you remembered seeing a plane crash on TV, you might draw the conclusion that air travel is unsafe and choose to travel by car … even though you’re far more likely to experience an auto accident than a plane crash.

Combating Your Biases

Recency bias often pushes investors to make “greed-based” mistakes. They assume whatever trend they are following will last forever.

Meanwhile, the availability bias will often push investors to make “fear-based” mistakes, avoiding profitable opportunities because of horror stories they’ve heard in the past.

And of course, sometimes recency and availability work together to force fear-based mistakes.

For example, the horror of the 2008 meltdown led to both recency and availability biases. That financial crisis pushed investors out of the market at exactly the time it was poised to enjoy an epic rally.

So what’s the takeaway here?

The theme for most of 2023 has been the resurgence of tech at the expense of virtually every other sector. Substantially, all of the gains of the S&P 500 in the first half of the year were due to the performance of the top six largest tech stocks.

But then a funny thing happened. The rally started to broaden. Non-tech stocks finally started to take the lead.

As traders, we need to be aware of our biases so that we can better conquer them.

Mike Carr is someone who focuses on the data when it comes to investing smarter and more efficiently. So if you want to learn more about how he trades (and get his expertise), check out his Trade Room today.

Regards, Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge

Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge