I wonder what the legendary science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov would say about the evolution of today’s robotic technologies…

I remember perusing Asimov’s most famous novel, I Robot (first published in 1950), as a junior high school student back in the dark ages of the late 1970s. Back then, industrial robots were just beginning to take to the factory floor in growing numbers. But the book was already famous for expounding what are sometimes called the “Three Laws of Robotics,” or more simply, “Asimov’s Laws.”

The first law states: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Asimov meant physical harm. But what about humans coming to economic harm?

We have a name for that, of course. It’s called capitalism. It’s the reason we can even talk about robots as something other than science fiction today in the first place.

But here’s what has me ruminating on the subject: Sometime in the next few months, Adidas — the world’s third-largest maker of sneakers — said it will power up its first Speedfactory in Ansbach, Germany — a manufacturing operation staffed entirely by robots with about a dozen human technicians.

To me, that’s earthshaking news for the future of employment.

Sure, it may not affect Americans much … at first (of all the major sneaker makers, only one — New Balance — still makes sneakers in the United States).

But just wait. Think bigger. Think of the proverbial forest instead of just a couple of trees…

Winning the Wage War

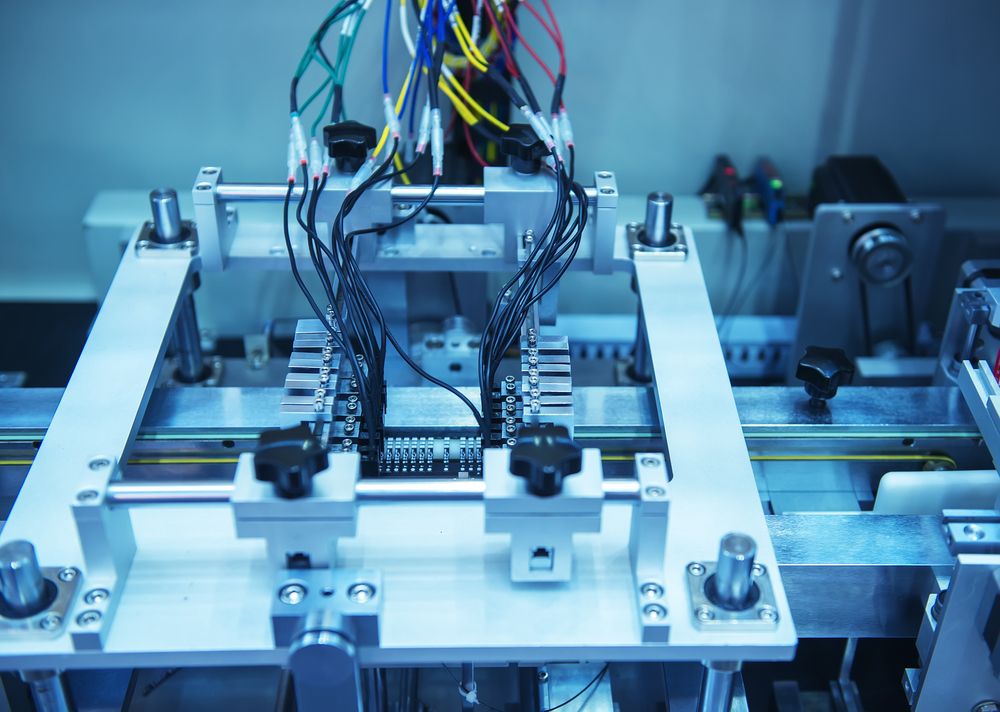

Until now, the making of a pair of sneakers was one of those tasks that largely defied the abilities of industrial robots. Machines just didn’t have the dexterity and finesse to handle and position the sneaker’s fabric and foam rubber components, not to mention sewing and gluing them all together.

Score one for the humans!

Even though sneaker making is a low-wage job, often done in unpleasant sweat-shop-style conditions, it provided employment to millions in Asia at the bottom of the economic ladder. The only problem: Humans have this highly annoying habit of wanting to get paid more, in terms of money and benefits as time goes by.

That’s what’s been happening in China and elsewhere in recent years. In 2014, a prolonged labor dispute at a contract manufacturer in Dongguan, in southern China, held up sneaker production for Adidas and other companies for weeks as 40,000 workers stayed off their jobs in protest.

Labor strife is a major new phenomenon in China (where independent trade unions are illegal). But workers, thanks to social media, have been able to communicate and organize anyway — even when police arrest and cart off the most vocal leaders.

As a result, the number of worker protests is rising. The China Labor Bulletin tracked 1,400 strikes in 2014, and more than 2,700 last year.

Vietnam is a huge production center too, these days. Nike alone employs more than 300,000 people there. The country is not immune to strikes. Last year, as many as 90,000 workers at a contract manufacturing plant in Saigon (sorry, I still can’t call it Ho Chi Minh City) went out on strike. The facility churns out millions of pairs of shoes each year for Nike, Adidas and others.

Now along comes Adidas’ robotic sneaker-making effort.

The sporting goods maker says it has two goals for its Speedfactory. One is to cut the length of time it takes to design a new shoe, put it into production and get it out to “fast fashion” shoe buyers. The other is to cut its freight costs from Asia.

Left unsaid is that by doing so, a sneaker maker cuts much of its labor costs too. Each pair of $100 sneakers costs roughly $25 to make in Asia, and another $3.50 to ship across the ocean.

Imagine how much more money Adidas would make if it shifted even a small percentage of its sneaker-making capacity from Asia, to say, Detroit (one company executive said that’s where the company was looking to place its first U.S. robotic sneaker factory).

The American Worker Pays a Steep Price

Does the return to the U.S. mean a revival of American shoemaking? Not unless you’re a highly skilled technician or engineer in robotics and automated factory environments.

According to Adidas, the Speedfactory would employ just 10 humans to service and maintain their robotic overlords.

The bigger point of all this is that robotics, which have long been used to replace expensive, skilled workers (such as spot welders and machinists), are now moving into some of the most unskilled, labor-intensive job categories.

It all speaks to a key Sovereign Society theme of technology keeping downward pressure on wages. Amazon has a labor force of more than 200,000, yet also owns its own line of expensive “warehouse picker” robots. It has options if its human workers start costing too much, eating into the company’s already thin margins.

And if sneaker makers can successfully churn out thousands of pairs of robotically made “Flyknit Air Max” running shoes (yeah, I know that’s a Nike brand; they’re on the path toward robotic factories too), can apparel makers be far behind, or fruit and vegetable picking for that matter? What about all the folks who do all the stocking of boxes on the shelves of the big-box and grocery stores at night when most of us are asleep?

We are moving into a new period that would likely give Isaac Asimov a whole lot more to write about in the coming age of robots. The future is grim for the American worker. The U.S. is already facing the specter of recession yet again as the manufacturing sector weakens and our so-called jobs recovery was really a sham in which we swapped high-paying, middle-class jobs with low-paying, service sector and temporary jobs. Add in robots scooping up more jobs and the future becomes even bleaker.

Kind regards,

JL Yastine

Editorial Director, The Sovereign Society