Article Highlights:

- To forecast the 2020s, I looked way back to the 1820s.

- My strategy delivered a gain even as prices fell almost 20%.

- I’ll reveal more at this week’s Total Wealth Symposium.

There’s an old saying: “Those who fail to study history are doomed to repeat it.”

The truth is that few people study history. So, we’re doomed to repeat it.

Taking a historical approach to the markets isn’t easy, though.

I study economics, financial theory, politics and sociology to make sense of market history.

At Banyan Hill’s annual Total Wealth Symposium this week, I’ll explain what history tells us to expect in the 2020s.

But today, I have a simple strategy for you that makes money in any market.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

To forecast the 2020s, I looked way back to the 1820s.

In 1820, there was a presidential election. Voters worried about tariffs and monetary policy.

Relations with the United Kingdom and Europe were a hot topic. So was the role the U.S. should play in the world.

Let’s jump ahead to the 1920s. Tariffs were again an issue. The U.S. was busy isolating itself from the U.K. and Europe.

In the 1920s, voters didn’t talk about monetary policy. But the newly formed Federal Reserve was fighting amongst itself about policy.

By 1930, regional conflicts split the Fed. That conflict was probably the most important factor in turning a recession into the Great Depression.

You can see that studying history helps put current events in perspective. The specifics are a little different today, but the general issues are the same.

Investment Lessons From the 1820s

History isn’t just interesting. It’s also instructive.

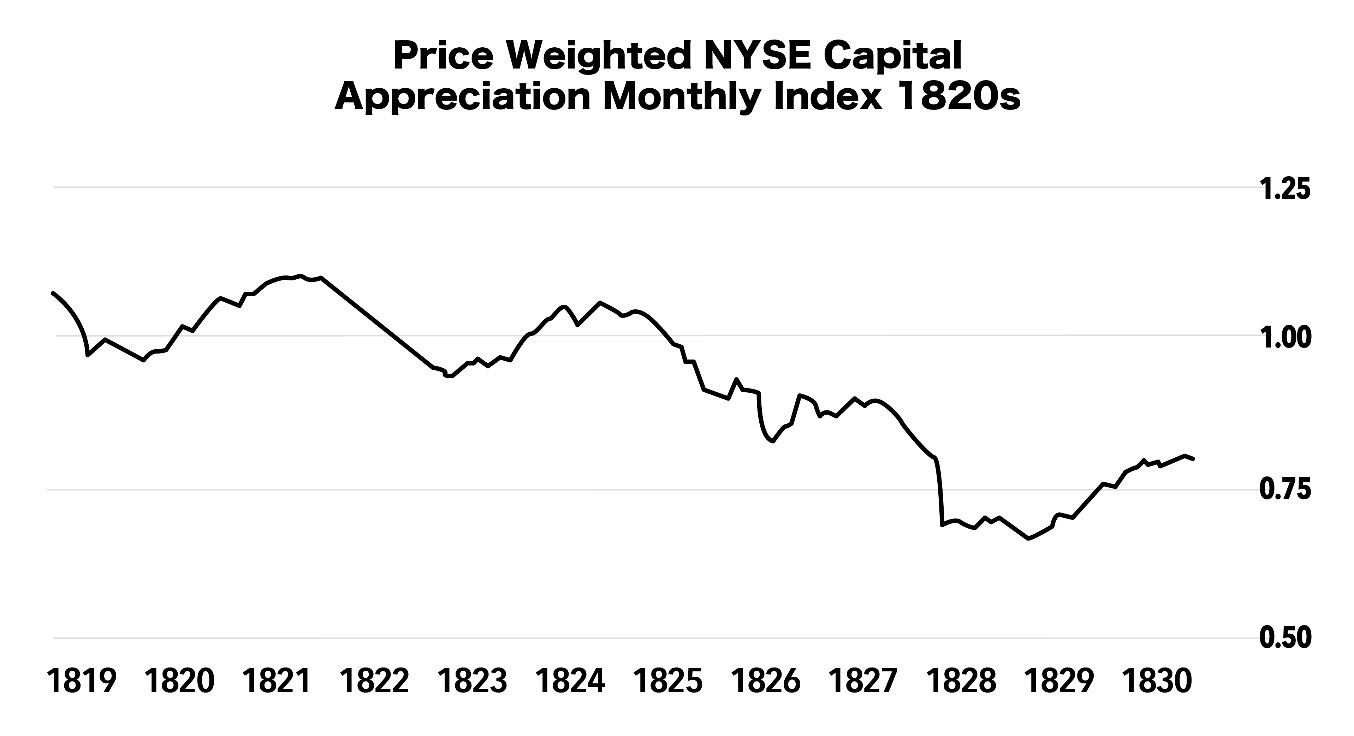

To see why, let’s look at a chart of the stock market action in the 1820s.

At first glance, it’s obvious this is a downtrend. But investors at that time didn’t really care much about prices.

In the 1820s, investors bought stocks for dividends. Available data indicates annual yields averaged 5.8% during that time.

Because of high dividends, investors were patient. Trading activity was low in the 1820s. Stocks back then traded by appointment.

Exchange officials ran through a roll call of stocks twice a day. Anyone wanting to buy or sell provided a quote when the stock’s name was called. Little trading occurred most days.

But the low trading volume did result in some price swings.

I found a strategy that profited from the price swings, even in a downtrend.

Trading was infrequent, so my strategy needed to be infrequent. To meet that goal, I looked at trading once a month at the most.

I found that a simple idea worked well — wait for the sellers to finish. Prices always stop falling when we run out of sellers.

That’s not a glib observation. Here’s a precise trading strategy you can apply:

- Buy on the first of the month after prices decline three months in a row — but only when the range is smaller than it was in the previous month. (The range is the difference between the high and low in the month.)

- Sell after one month.

This simple strategy beat the market in the 1820s. It delivered a gain even as prices fell almost 20%.

Withstanding the Test of Time

This strategy also worked after the 1820s.

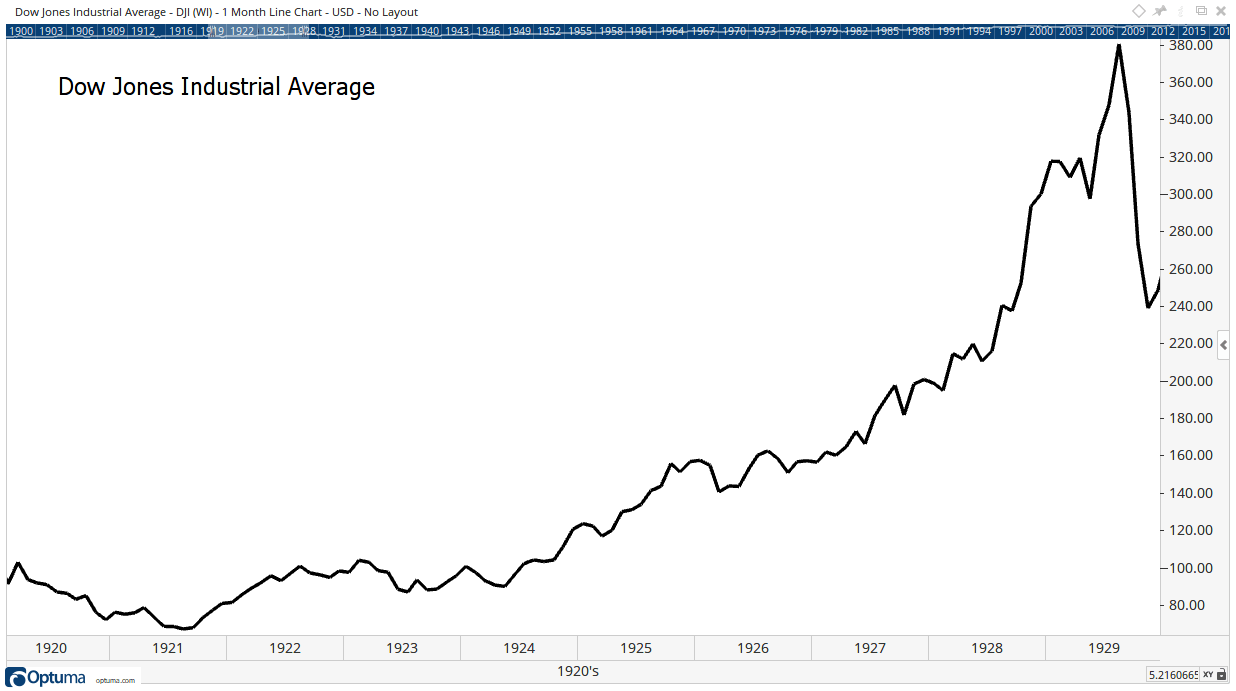

It delivered winning trades in strong bull markets, such as when stocks roared higher in the 1920s.

The 1921-1929 Bull Market

This simple trading strategy delivered wins about 75% of the time in both bull and bear markets. The average monthly gain is about 2.4%.

It ignores the fact that markets have changed in the past 200 years.

Stocks now trade more than twice a day. They trade continuously.

Professional investors can trade from Sunday night through Friday afternoon without any breaks.

For traders, this means there are more opportunities. They can use this monthly strategy often.

But there are even better trading systems. I’ll reveal them at the Total Wealth Symposium.

Regards,

Michael Carr, CMT, CFTe

Editor, Peak Velocity Trader