Small individual investors, like you and me, don’t have many advantages over large institutions.

But as counterintuitive as it might sound, our small size is a huge one.

Institutional investors have deep pockets. They can fund research teams with dozens of Ph.D.s. They can fund lobbyist groups that work to bend regulations toward their favor. They can co-locate their technology with the exchanges’ … ensuring their orders get filled faster and at better prices than ours do.

The list goes on … and makes for a compelling counter-argument.

But my friend and colleague Mike Carr made a great point recently, arguing that you and I aren’t Warren Buffett … so we shouldn’t try to be.

Mike says that, because Buffett is one of the largest money managers in the game, he has access to opportunities the “little guys,” like us, could only dream of.

Think of it this way… More than a dozen private jets reportedly landed in Omaha as the banking crisis erupted in mid-March. How many landed outside your home?

But even if we can’t invest the way Warren Buffett does, our small size allows us opportunities he could never touch.

The Oracle of Omaha has even admitted this himself once, saying:

Anyone who says that size does not hurt investment performance is wrong. The highest rates of return I’ve ever achieved were in the 1950s – but I was investing peanuts then.

It’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money.

See, Buffett manages hundreds of billions of dollars. That means he can’t touch “small” stocks with a 10-foot pole … even when he wants to.

This is a blessing for small investors. It means there’s a whole sector of investment opportunity that can make a big impact on your wealth early on … and an even bigger impact once those stocks grow enough to attract institutional attention.

And who do we have to thank but the SEC for affording us the best of the best of these opportunities…

Small Caps and the $5 Rule

Nearly a century ago, the SEC established a frankly ridiculous rule which makes it a real pain for any big investor to buy a certain class of small-cap stocks.

(If you’re already familiar with small caps, feel free to skip down to the next section where I talk about this rule in-depth. Otherwise, read on for a quick primer.)

Stocks are generally categorized by their market capitalizations, or “market cap.” A stock’s market cap is simply it’s per-share price multiplied by the number of shares it has outstanding.

Stocks with a market cap above $10 billion are considered large-cap stocks. $2 billion to $10 billion makes up the mid-cap category. This is the sandbox where the big money plays.

$250 million to $2 billion is the “small-cap” space. And companies with market caps under $250 million are called micro-caps.

Effectively, the entire micro- and small-cap categories of stock are off-limits to Buffett and his peers. Even when he sees an attractive opportunity there, he knows the size of his investment would be too small to matter … or that he would move the market if he invested a meaningful amount of capital.

At the end of the day, Buffett knows he can’t touch small stocks. I doubt he bothers to even look at them these days, because even if he does … he has to “pass.”

Of course, Buffett is just the prototypical large institutional investor — he is far from the only one.

Hundreds of mutual funds, hedge funds, pensions, endowments and insurance companies face the exact same “size penalty.” They’re too big to invest in the best small-cap companies.

Many of those large investors even have rigid rules written into their charters and mandates, absolutely prohibiting them from investing in companies that are too small, either on the basis of market cap or a stock’s per-share price.

In fact, one of the “silliest,” yet highly exploitable anomalies related to the size of a stock is what I call “The $5 Rule.”

Exploiting the $5 Rule

The $5 Rule dates back to SEC regulation that was written in the 1930s, creating additional hurdles institutional investors must jump through when buying a stock that’s priced below $5 a share.

The $5 threshold is, as far as I can tell, completely arbitrary. There is no meaningful difference between a stock that’s priced at $4.99 and one priced at $5.01.

Yet, in the eyes of the SEC, and the institutional investors subject to the $5 Rule, there is a difference.

$5.01 and above, stocks are “fair game.” $4.99 and below, stocks are effectively “off limits.”

And that’s why I’m saying the little guys like us have a meaningful advantage over the big boys. When we find a high-quality company whose stock trades for less than $5 … we can buy it just as easily as a stock that trades for $50.

While the stock trades below that threshold, we have little competition from the Wall Street machine and its biggest players.

Most institutions won’t touch a stock while it’s under $5. So, many analysts don’t bother covering it.

And that leaves a trove of high-quality companies that go overlooked, undiscovered or untouched … simply because they’re “too small,” according to that arbitrary $5 rule.

And here’s the most beautiful part of it all…

Once a stock that was previously below $5 crosses above that threshold … Wall Street’s handcuffs are off. Analysts, portfolio managers and allocators can all jump back in.

And when they do, sometimes all at once, it can send prices dramatically higher.

At this point, the investor who’s read one too many Berkshire Hathaway annual letters may be reading this and thumbing their nose at the risks associated with small-cap stocks.

Well, you’re right. Those risks exist.

But when you invest the way I do, you know how to mitigate those risks … and find only the small-cap stocks with the highest odds of success.

The Right Way to Find Great Small-Caps

Most academic research has rightfully focused on market cap as a measure of size than the per-share price, though there’s quite a bit of overlap.

Stocks that trade for less than $5 a share are generally on the smaller side of the market cap spectrum.

Indeed, there are risks that come with investing in small-cap stocks. Relative to large companies, small companies typically are characterized by the following:

- A smaller capital base, reducing their ability to deal with economic uncertainty.

- Greater volatility of earnings.

- Greater uncertainty of cash flows.

- Less depth of management.

- Less proven business models (in some cases).

- Less information availability, due to fewer analysts covering them.

- Greater volatility of share price.

Of course, unless you for some reason believe in “free lunches,” the unique risks that come with investing in smaller companies is precisely why investing in smaller companies offers a higher return.

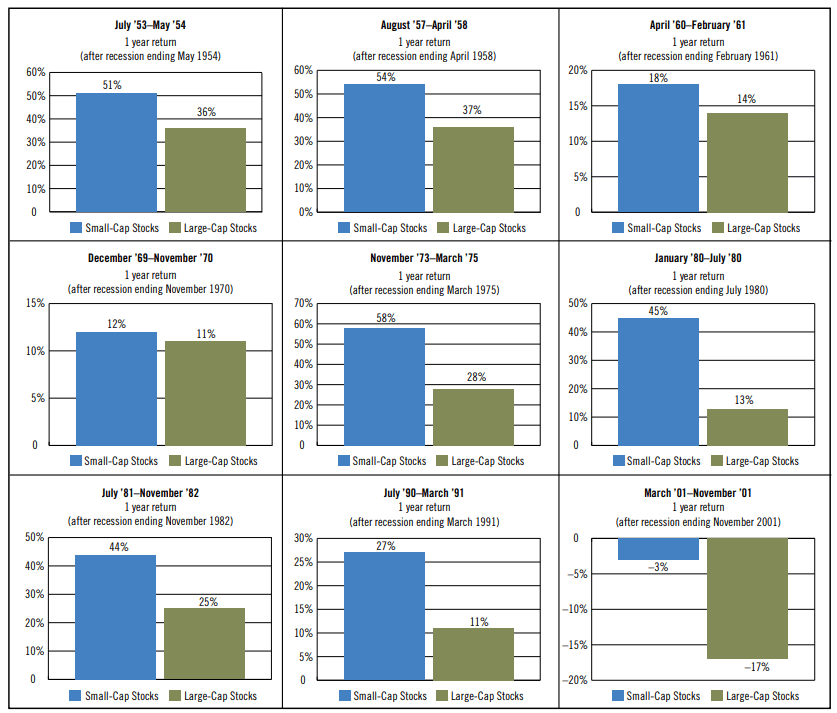

Over the long arc of market history, small-cap stocks have outperformed large-cap stocks.

A large number of research studies on U.S. stocks, as well as foreign developed and emerging-market stocks, have shown this is true.

It’s also true over various time frames, some stretching all the way back to the 1920s.

Of course, U.S. large- and mega-cap stocks had a fantastic run during the middle- and late-stages of the last bull market. And that’s why everyone I talk with seems unaware of the long-run advantage to buying smaller companies.

It’s also why I’m on a mission to educate readers on this advantage … and why I’m biasing the portfolios I build in my stock research services — Green Zone Fortunes and 10X Stocks — to the “small” side.

Particularly since now is the perfect time to be building an overweight “small-cap” portfolio…

While small-cap stocks in general, and low-quality small caps in particular, tend to experience outsized volatility during bear markets and recessions…

That volatility represents buying opportunities, particularly in the type of high-quality small-cap companies that tend to outperform like gangbusters in the wake of a recessionary pullback.

Consider this chart from a Prudential study, which shows small-caps have outperformed large-cap stocks following the last nine recessions…

That’s why I’m gearing up for what I expect to be a massive run of outperformance in small, high-quality companies over the next two to three years.

The bear market is creating this once-in-a-decade opportunity to buy small companies at deeply discounted prices — many of them for less than $5 a share, Wall Street’s “off limits” threshold.

And using my Stock Power Ratings system, I’m able to screen out only the most high-quality small-cap stocks from the names that present more risk than reward.

I‘ll share more specifics on that soon. But here’s the big takeaway.

These opportunities are simply not available to Warren Buffett or his friends …

It’s only for to the “little guys,” like you and me.

And I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to pounce and take advantage of it!

Regards, Adam O’DellChief Investment Strategist, Money & Markets

Adam O’DellChief Investment Strategist, Money & Markets

P.S. In the coming weeks, I’ll share more about my research thus far on sub-$5 small-cap stocks … including a report of potential candidates that I’ll share completely for free.

We’re working on the final list now, but it’s looking like upwards of 300 names for you to check out. Keep an eye out for that next week.

In the meantime — tell me, did I sway your opinion on small-cap stocks, if you held a negative opinion to begin with?

Write me at BanyanEdge@BanyanHill.com with your thoughts.

The March Banking Scare: What’s the Damage?

In yesterday’s Edge, Mike Carr characterized last month’s banking scare as a “black-necked swan,” rather than a black swan.

Meaning, it looked like a scary, widespread event in the banking sector. But on closer inspection, it’s not likely to blow up the world.

I actually agree with Mike.

However, that doesn’t mean there won’t be consequences.

A banking system that is fixated on strengthening its balance sheets — and stopping a flood of clients from running out the door — is not a banking system making loans.

And every loan not being made represents a business that might not get the capital it needs to launch, grow or add staff.

It’s far too early to say for sure, but it does appear that initial jobless claims popped in March.

We’ll know more as the April data rolls in.

It could be that the economy still has enough momentum behind it to shrug off the effects of bank tightening. But as I’ve been writing all year, the yield curve is deeply inverted, which has historically been a predictor of a pending recession.

It wouldn’t be hard to see March’s bank scare as a catalyst — one that finally tips us into recession.

We’ll see. In the meantime, we still have to capitalize on the opportunities in this market.

Adam makes a great point about how small-cap stocks fare in recessions, historically. Ian King’s found similar to support that idea. Like back in January, when he gave you five reasons to buy small caps in a bear market.

Like Adam’s coming report on sub-$5 small-cap stocks (which you don’t want to miss out on), Ian also knows the value of small caps. In his Extreme Fortunes service, for example, he explores tech companies in this market cap that are in disruptive markets. And they’re getting ready to soar by 500% — up to 1,000% within a few years.

If you want to learn more about Extreme Fortunes, go here to watch Ian King’s free presentation about the next “Convergence” in small caps.

And next week, you’ll hear more about Adam O’Dell’s $5 small-cap plays.

Regards, Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge

Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge