I always get a jolt when someone says: “Many investors today have never lived through XXX” … where XXX is something I experienced in real time.

Take the subprime mortgage crisis, which culminated in a spectacular market crash just 14 years ago.

I had just returned to the U.S. after years of living in South Africa. I’d been away so long that my credit score was zero.

A year before I arrived — 2007 — that would have got me a jumbo mortgage. After the financial system collapsed, I could barely open a checking account.

This experience is etched into my memory. But for younger Americans, it’s not the same.

A 30-year-old investor would have been 16 at the time. A 25-year-old would have been 11. If either noticed the crisis, it was likely only because their parents were grumpier than usual.

Many young investors are only dimly aware of the subprime mortgage crisis and the dot-com bust.

They can’t imagine a world with conditions like those. They take recent circumstances for granted.

Now there’s another big shift underway … one that could be far more consequential for the economy, our politics and our pocketbooks than either of those two events.

I’m talking about the collapse of globalization…

Booming Trade Transformed the American Experience

“Globalization” is the most consequential economic development in the lifetime of anyone born before about 1985.

Yet, most people take it for granted — many even claim to oppose it.

The baby boomer generation (I squeaked in at the very end) experienced an unprecedented growth of world trade. It changed our lives in ways younger generations struggle to understand.

From 1948 to 1970, trade volumes were tiny. But as colonial empires crumbled and Europe recovered from the Second World War, trade surged.

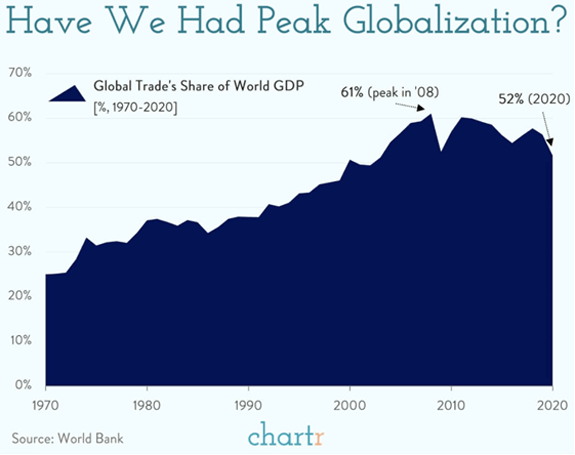

By 1980, cross-border trade was worth $2 trillion (37% of world GDP). It hit $4 trillion in 1993 (42% of world GDP) the year Bill Clinton took office.

Clinton made free trade — including China’s membership in the World Trade Organization — a centerpiece of his foreign policy.

When he left office in 2001, global trade was 50% of world gross domestic product (GDP). Thanks to his policies, by 2008, $0.61 out of every dollar of global economic output was attributable to international economic activity:

(Click here to view larger image.)

Here’s what those of us who were there experienced:

- As kids, almost everything we consumed was made in America by Americans. Now we spend $700 billion a year on foreign-made goods.

- The U.S. went from being the leading exporter to having a massive trade deficit.

- Millions of Americans lost their jobs because their employers could hire cheaper workers abroad.

- Thanks to cheap imports, prices fell steadily, allowing American living standards to rise even as wages stagnated.

- Because most global trade is in dollars, demand for the greenback has kept our currency artificially high, making our exports uncompetitive.

- The increased profitability of global U.S. companies made Wall Street the world’s premier financial center … and sent U.S. stocks soaring.

Obviously, globalization had winners (companies, Wall Street) and losers (workers).

The big question is whether reversing it would undo those outcomes … or make things worse.

Lopsided Globalization

Capitalist free markets are supposed to produce the most efficient use of resources and the lowest prices. Tariffs, quotas and other barriers to global trade prevent that.

So, globalization is really the process of getting rid of those barriers. Increased trade as percentage of GDP is the result.

The problem is that in practice, globalization only applies to capital.

U.S. companies can easily shift their supply chains or even their whole operations overseas. The same is true of foreign companies who want to do business here.

But workers — the other essential economic input besides capital and raw materials — enjoy no such freedom. Money can move freely, but human beings are trapped inside the boundaries of whatever nation in which they happen to be born.

That’s produced two trends that have undermined globalization … even before a global pandemic and geopolitical tensions disrupted the world economy.

The first is a dramatic fall in economic, social and political status for workers in the developed world, as their jobs, salaries and life prospects have been exported to countries like China.

The second is an equally dramatic increase in inequality, as those who control the capital that can move freely pull ever farther up and away from wage-earners stuck wherever they happen to be.

In other words, globalization as practiced since the 1990s has contained the seeds of its own destruction.

But which would be better: reversing globalization … or reforming it?

The Devil You Don’t Know

I make no bones about the fact that I’m on the side of reforming globalization. Either we make it more equitable … or we return to a fragmented global economy.

Here’s what that would mean:

- Prices of many consumer goods would rise permanently, reflecting higher domestic costs of production.

- Government would have to intervene massively in the economy to protect domestic industries and regulate trade. If you think we have “Big Government” now, just wait.

- Employers would depend entirely on the domestic workforce, empowering the latter to demand higher wages and benefits. That would compound price inflation, reduce capital investment and slow economic growth.

- Governments would have to introduce capital controls to force savings to remain inside the country. That would lead to a huge drop in international equity investment flows, depressing stock prices.

- Capital controls would also limit the government’s ability to run deficits, since it would rely on domestic financial markets to purchase Treasury bonds. That would also lead to a significant increase in interest rates, slowing economic growth.

All the above is a recipe for permanent stagflation, political instability … and a stagnant stock market.

Thanks to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we’re experiencing a foretaste of a deglobalized world economy. Let’s hope the powers that be don’t draw the wrong lesson from it.

Kind regards,

Ted Bauman

Editor, The Bauman Letter