I receive emails all the time from people who say: “I only want to invest in safe stocks with a good dividend.”

That’s great. But what’s “safe” in one market cycle isn’t always safe in another.

And when it comes to income investing, the rule of thumb is when the “safe” reputation of a stock disappears, so do investors’ dividend payments.

So add a new word to your income investor vocabulary: sustainability.

That’s especially the case if you enroll in a dividend reinvestment plan (or DRIP for short).

In a dividend reinvestment plan, investors’ dividend payments are automatically steered back into the purchase of yet more shares of stock, quarter after quarter.

It’s a great way to build tremendous wealth over years’ worth of time, as the company grows and the value of the investor’s holdings and dividend payments grow with it. But if the company’s dividend turns out not to be sustainable, neither is the strategy.

A Dead-End Dividend

Case in point: the ongoing travails of General Electric Co. (NYSE: GE).

To individual investors, GE was considered, until very recently, perhaps the safest of safe stocks.

After all, GE’s been a member of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for the entire 122-year history of the index. It has survived booms and busts from the industrial era right up to the digital era.

And from its flows of excess cash, GE paid dividends to a legion of investors for nearly its entire existence. Until last year, GE only cut its dividend on two occasions, both of them economic national emergencies — the Great Depression, and 70-plus years later, the more recent Great Recession.

But this is where a dividend’s sustainability comes into play. Companies change. Economies change. Yesterday’s “safe” stock becomes tomorrow’s rabbit hole of value.

It’s All About Cash Flow

In Total Wealth Insider, we have a handful of DRIP-style stocks that continue to throw off robust amounts of excess cash. It all but guarantees dividend sustainability as they pay generous amounts of that cash back to shareholders in the form of steady, rising dividend payments for years to come.

Companies pay their dividends from the excess cash generated by their business. So I use a measure called free-cash-flow yield to gauge whether a company’s operations are healthy enough to keep paying (and hopefully raising) the dividend in coming years.

You can figure out free-cash-flow yield for any public company. Take free cash flow — published by all companies in their annual and quarterly financials — and divide that number by the company’s total enterprise value.

What you get is a figure that shows you what percentage of your stock’s value is created by the cash generated by its business operations.

In other words, if a company reported $200 million in free cash flow last year, and its market value was, say $3 billion, then it had a free-cash-flow yield of 6.7%.

Picture of Financial Health?

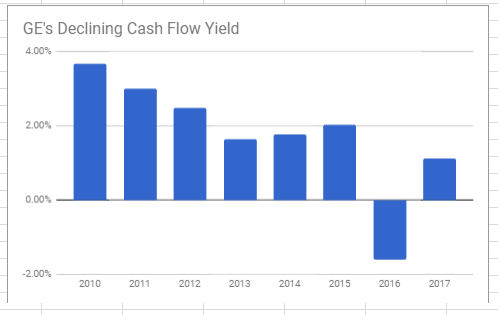

The specific number isn’t so important in my view as the overall trend as you calculate the same cash-flow yield for past years as well.

In the case of GE, it shows us a company whose collection of businesses was generating smaller and smaller amounts of cash each year, relative to GE’s debt-swelled total enterprise value of $214 billion.

(Source: Capital IQ data)

As you can see from the chart, it was only a matter of time before GE needed to cut its dividend. It couldn’t afford to keep returning that much cash back to its shareholders every year.

Sooner or later, the company would face a situation where it needed those funds more urgently to reinvest into its own operations (with the goal of reinvigorating its growth) rather than shuffle the money out to its shareholders each quarter.

And where does that leave income investors, especially those with an eye on long-term wealth-building through DRIP-style investing?

It leaves them hanging over a cliff, waiting to see whether GE’s turnaround plan works, and with the unlikely hope for a potential restoration of a larger dividend at some future date.

They learned the hard way that paying a dividend and sustaining that dividend while continuing to raise it for years at a time — are two different things.

Kind regards,

Jeff L. Yastine

Editor, Total Wealth Insider