This year I tightened my belt. Literally.

I’ve lost 40 pounds since January.

People who haven’t seen me in a while ask me how I did it.

It was simple. I gave up some things and adopted others.

But simple doesn’t mean easy.

At first, it was tough to forgo almost all carbohydrates except those from vegetables … especially from a guy renowned for his pasta dishes.

And my breakup with rice was especially poignant, given my love of South and Southeast Asian food.

But I made the changes — and today I’m better for it.

The Federal Reserve’s recent hawkish turn suggests a different kind of belt-tightening is just around the corner.

Just as I had to give up some things to achieve the goal of a stable, healthy me, financial markets must make some changes if the Fed starts tightening interest rates.

What are they likely to be, and how could they affect your portfolio?

In Credit We Trust

Today, credit mediates a much larger proportion of U.S. economic activity than in decades past.

Before World War II, people rarely took out mortgages to buy homes. They saved their money, and when they had enough, they bought one. The same was true of other asset purchases, like automobiles, farm machinery or appliances.

Starting in the 1950s, banks created credit products that allowed people to buy before they earned. That’s been a key feature of the U.S. economy ever since.

Today, the financial sector’s contribution to GDP is more than twice what it was in the 1960s.

This increased “financialization” has made every asset market highly sensitive to changes in interest rates, because they affect the yield and financial value of those assets.

Ever since the Fed engineered ultra-low interest rates after the great financial crisis (GFC), credit has been cheap and accessible (at least to those who qualify).

When the cost of credit falls, the price people are willing to pay for assets bought with it increases.

That’s why easy Fed money has led to rising prices in three key markets: public equity, private equity and housing.

The problem is that if the Fed starts hiking rates, those asset prices will move in the opposite direction.

Public Equity: The Stock Market

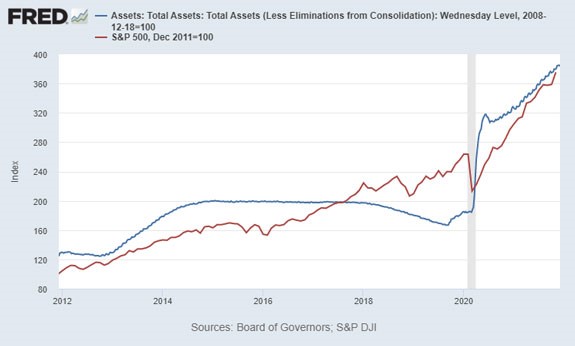

The more the Fed engineers low interest rates by buying Treasury bonds, the higher stock prices go:

(Click here to view larger image.)

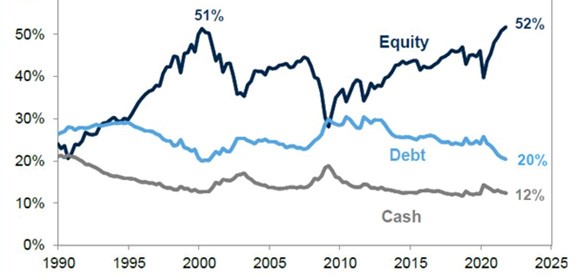

Low interest rates make it impossible to earn returns anywhere else. So, people increase their exposure to stocks:

U.S. Financial Asset Allocation, 1990-Present

(Click here to view larger image.)

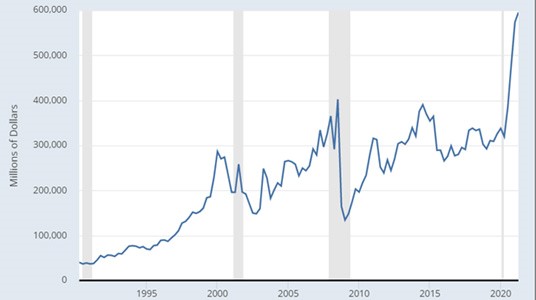

An even more direct mechanism is when people borrow money to buy stocks on margin. Margin accounts at U.S. brokerages have risen steadily since the GFC, but have skyrocketed since last year:

Margin Account Balances at U.S. Brokers and Dealers

(Click here to view larger image.)

The bottom line is that cheap money increases the prices people are willing to pay for stocks.

Eventually, those prices become unrealistic relative to future earnings.

If interest rates rise, and alternative investments become more attractive, those prices can come crashing down.

Consider how quickly earnings at three highly valued companies would need to rise over the next five years to justify their current valuations:

| Stock | P/E | Required annual 5-year earnings growth | Actual earnings growth, last 3 years |

| Tesla | 320 | 70% | 45% |

| NVIDIA | 89 | 24% | 17% |

| Salesforce.com | 141 | 36% | 20% |

None of these companies are growing fast enough to meet those targets. That makes them exceptionally vulnerable to rising interest rates.

Private Equity

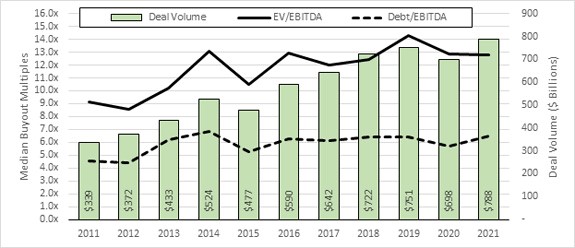

Private deal makers tap credit markets to buy companies in the hopes of reselling them for a profit. The chart below shows that the cheaper and more abundant credit is:

- The greater the volume of private equity deals.

- The more dealmakers are prepared to pay for earnings.

- The more debt is loaded onto the target companies.

(Click here to view larger image.)

If interest rates rise, servicing this debt will become more expensive, cutting earnings at the target company.

That will make their valuations unrealistic, leading creditors to make loans tougher to get.

If interest rates rise quickly, some of these companies could go bankrupt. If it happens to a lot of them, we could see a systemic credit crisis and recession.

Housing

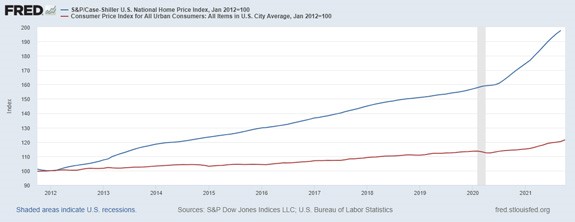

The effects of cheap credit really jump out in the housing market. Since 2012, the national home price index has nearly doubled — dramatically outpacing inflation:

(Click here to view larger image.)

Anyone who’s ever bought a house knows that the key variable is the monthly payment. As interest rates fall, house prices rise, keeping the monthly mortgage payment the same.

But it also works in the opposite direction. If interest rates rise, housing prices fall.

That wouldn’t necessarily be bad for the housing sector, since lower prices will attract more buyers. But it could leave those who bought near the market top underwater.

Start Shopping for Your New Financial Outfit Now

I’m not predicting a sudden crash in the stock market.

But there’s no avoiding the fact that if interest rates do rise significantly over the next decade — something the Fed has said it wants to happen — asset prices aren’t going to grow as fast as they have over the last decade.

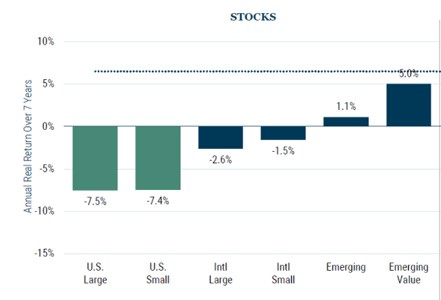

In fact, based on current macro fundamentals, annual returns to U.S. equities will probably be negative over the next seven years:

(Click here to view larger image.)

After I’d lost quite a bit of weight, I had to go out and shop for new clothes.

If credit markets are going to tighten over the next decade … as I’m convinced they will … you’re going to need to make some changes to your investment wardrobes (aka portfolios).

It’s never too early to start!

Kind regards,

Ted Bauman

Editor, The Bauman Letter