Investing is a lot like those terrible river-ferry disasters that seem to happen every few years.

Normally, people scatter themselves across a vessel’s deck, their weight distributed evenly throughout the ship. But if something should happen that causes many of them to rush to one side…

The ship tips over. Bad things happen.

The same thing happens in the markets every investing cycle. This time around, that boat might just be a phenomenon with a two-word name…

Passive investing.

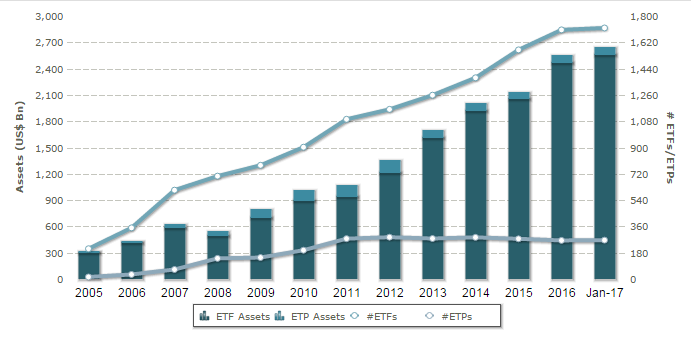

Passive investing means buying index-based exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or similar offerings from mutual fund families. Just looking at ETFs alone, their popularity is nothing short of phenomenal.

According to the research firm ETFGI, investors in the U.S. now have a record $2.64 trillion plugged into ETFs at the end of January, with the majority of it funneled into the major stock indexes such as the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq Composite.

(Source: ETFGI)

With the spate of new all-time highs posted by the major indexes, passive investors are well-rewarded for the strategy.

The level of assets in ETFs rose nearly 20% in 2016. And at the current pace this year (rising another 3% in January to the aforementioned $2.64 trillion), it’s quite possible ETF assets could rise another 20% or more in 2017 as well.

So what’s the big deal?

There’s nothing wrong with passive investing. It’s a smart, efficient way to seek a return on your money. But when too many people rush to one side of the investment ship, the risk is, well … you get the point.

Plenty of respected Wall Streeters have noted similar concerns. Recently, Baupost Group’s Seth Klarman, whose firm has more than $20 billion under management, noted

“the inherent irony” of market-efficient index-tracking ETFs and mutual funds: “The more people believe in it and correspondingly shun active management, the more inefficient the market is likely to become.”

Perhaps we can chalk it up to sour grapes.

After all, the success of passive-oriented index investing comes largely at the expense of active managers like Klarman. (Hedge funds certainly enjoyed their own heady success and bubble-like popularity, leading to their current “walk in the wilderness” period.)

My main point? We all know the “can’t miss” phenomenon by now. Before passive investing, it was real estate. Before that, it was dot-com stocks. Through much of the 1990s, the “Asian tigers” were all the investment rage. The list extends into the mists of stock market history.

But each of these, at some point, inevitably failed — leaving in its wake a legion of loss-wracked, disappointed investors. The faith in passive investing might just be the latest to come in for a sorely needed reality check.

Kind regards,

JL Yastine

Editorial Director