Natural gas is a highly cyclical commodity. We consume less than we produce in the summer and more than we produce in the winter.

In the warm months, companies produce natural gas from oil and gas wells all over the country. They clean it up to remove the water, sulfur and carbon dioxide. Then they pump it into giant caverns to store it for use.

In the cold months, companies take the extra gas out of storage and ship it to areas of high demand. Depending on the severity of the winter, the end of the drawdown usually occurs around the first week of April.

Natural gas prices should begin to head lower soon. If you own a producer, consider taking a profit or tightening up your stop. And there’s a countertrade that could make us double-digit gains as the price falls…

The Fall of Natural Gas

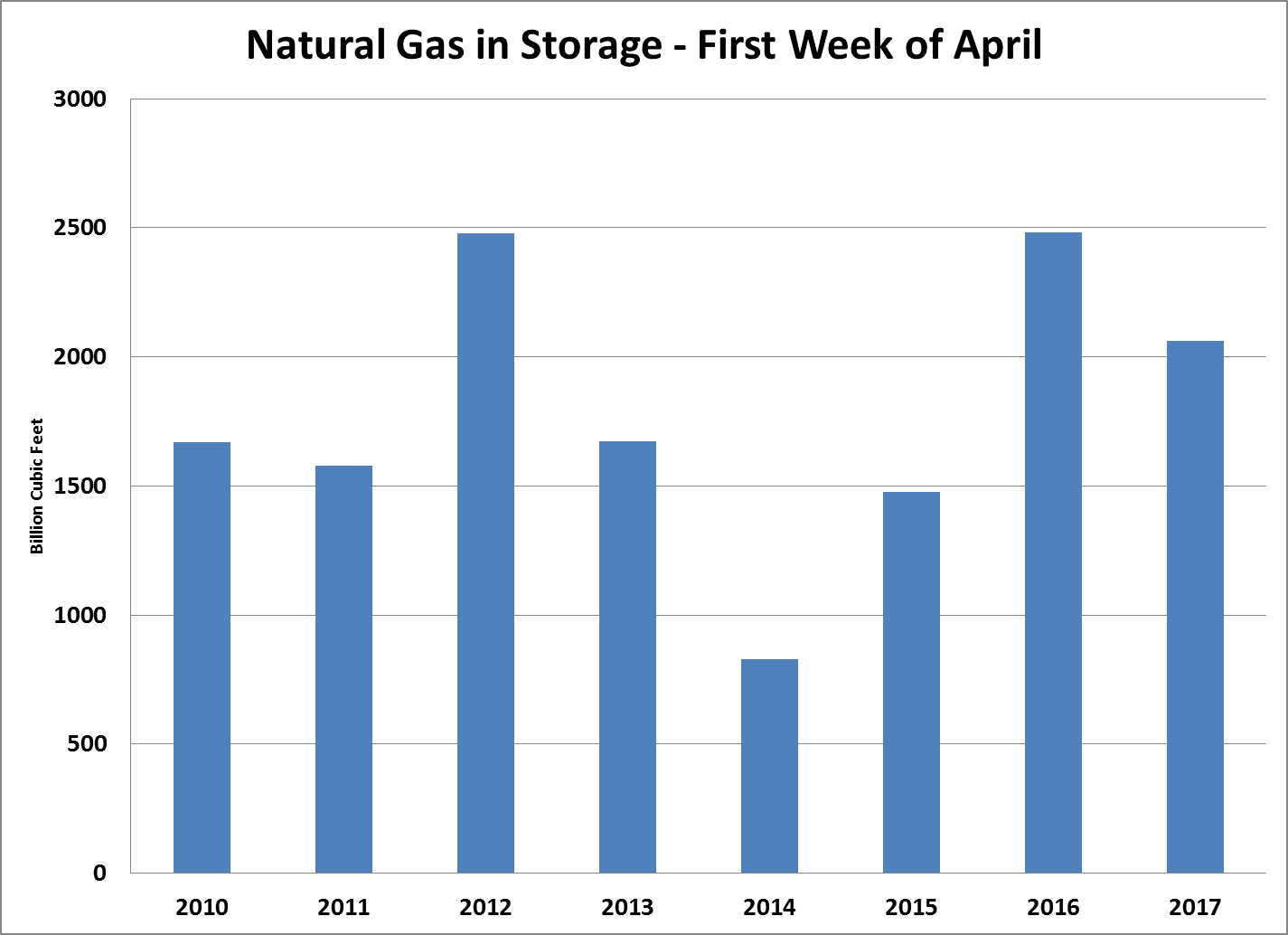

As you can see in the chart below, there is a lot of natural gas in storage:

(Source: data from the Energy Information Administration)

In November 2016, we hit a record volume of natural gas in storage: over 4 trillion cubic feet. The winter drawdown did not bring the level below 2 trillion cubic feet … the third highest volume of gas after a winter since 2010.

We have a lot of natural gas in storage. That’s because supply of natural gas overwhelmed demand for the last three years.

The natural gas market is different from oil. If the price of oil in the U.S. is cheap, you can put it on a ship and send it to a better market. Natural gas isn’t like that. To put it on a ship, you have to transform it into LNG, or liquefied natural gas, which requires a huge treatment and storage complex. Today, the LNG capacity of the U.S. isn’t large enough to affect supply and demand.

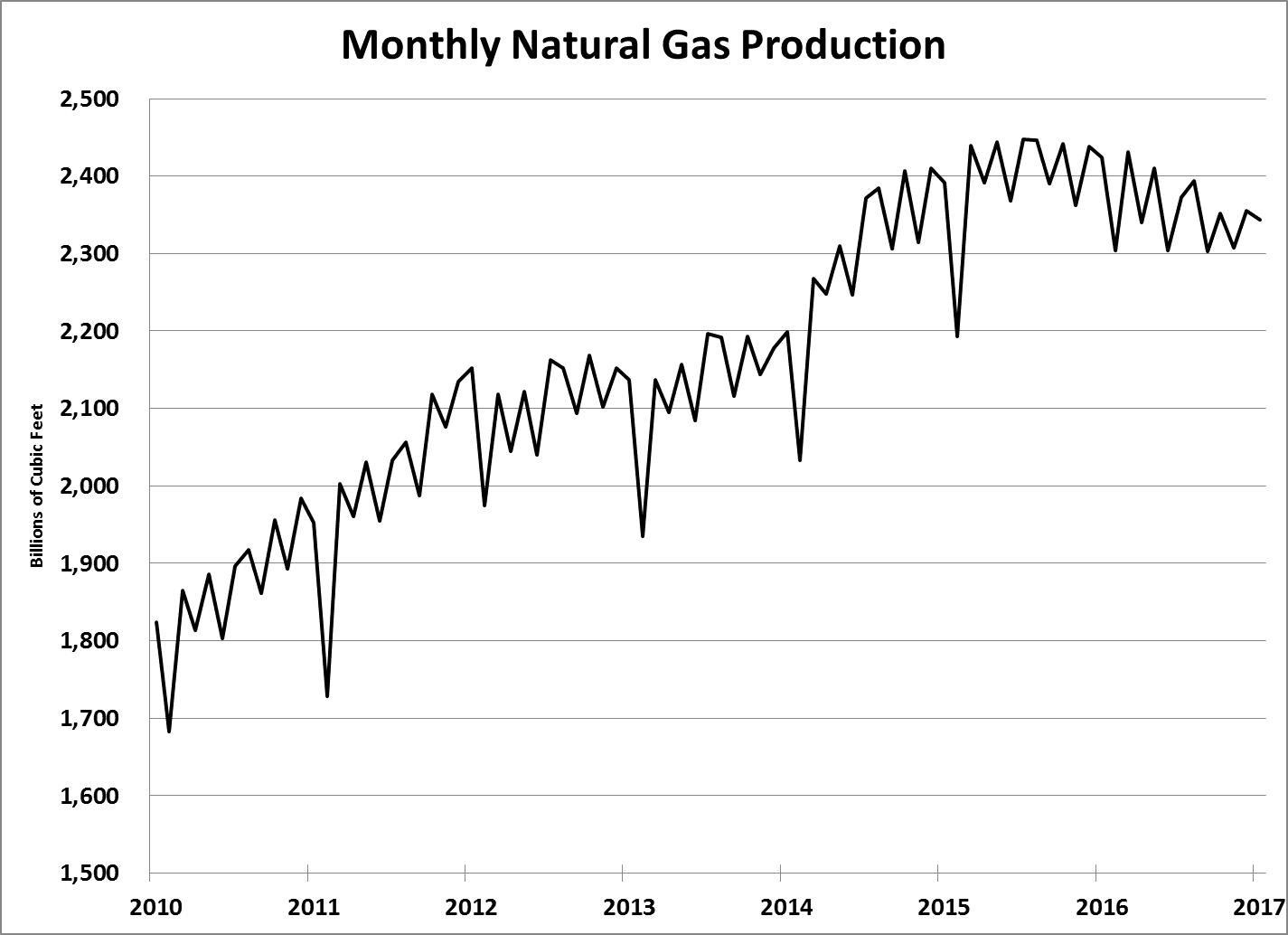

The supply of natural gas grew at an astounding rate thanks to our ability to crack shale rocks. Shale (thin beds of organic-rich rock) revolutionized the natural gas industry and supply. The graph below shows monthly U.S. gas production through January 2017 (the latest data available from the Energy Information Administration):

Production increased from 1,824 billion cubic feet in January 2010 to a peak of 2,448 billion cubic feet in November 2015. That’s a 34% supply increase in just five years. To put that in perspective, the annual consumption of natural gas only increased 14% over that period.

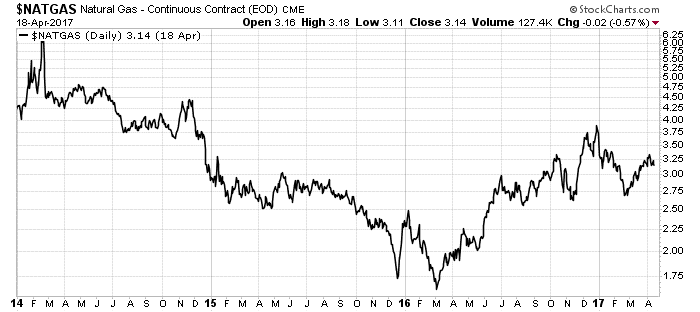

As you can imagine, that crushed the natural gas price. You can see what I mean in the chart below:

The price collapsed from over $6 per thousand cubic feet to under $1.75 per thousand cubic feet. That’s more than a 70% fall in price … a crushing blow to producers.

However, since the bottom in March 2016, the price rallied. You see, the fall in oil production affected natural gas too. Oil wells produce natural gas, so as companies quit drilling new oil wells, it reduced natural gas supply.

The natural gas rally saw the price rise over 80% to where it is today … but I believe that rally is over.

You see, the oil industry is back to work. Oil production bottomed back in September 2016. As it picks up, so will natural gas production. The higher price will encourage new production too.

A Recipe for Profits

In summary, we have a near-record amount of natural gas still in storage. We have high natural gas production that should rise. And we have a capped demand for natural gas.

Looks like a recipe for falling prices to me.

The best way for us to play falling natural gas prices is to short natural gas. We can do that with natural gas consumers. As the price of their fuel falls, their profits soar. That sends share prices soaring higher.

Terra Nitrogen Co. (NYSE: TNH) and CF Industries Holdings Inc. (NYSE: CF) use natural gas to make nitrogen fertilizer. As you can imagine, shares of Terra Nitrogen and CF Industries are down 36% and 57%, respectively, since May 2015. While the correlation isn’t perfect, shares of those companies could easily climb 15% to 20% as natural gas prices fall over the next few months.

Consumer trades are a great way to play natural resource bear markets. In my upcoming service, that will be one of my favorite strategies to use to take advantage of the normal declines in natural resource prices.

Good investing,

Matt Badiali

Senior Editor